The Androids of Tara

Doctor Who and the Androids of Tara

|

The Androids of Tara |

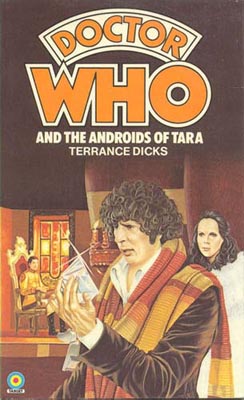

Target novelisation Doctor Who and the Androids of Tara |

|

| Author | Terrance Dicks |  |

| Published | 1980 | |

| ISBN | 0 426 20108 6 | |

| First Edition Cover | Andrew Skilleter |

| Back cover blurb: On a peaceful rural planet, where the colourful pageantry of old Ruritania mingles with ultra-modern Android technology, the Doctor becomes a king-maker in spite of himself. In his search for another segment of the Key to Time, the Doctor matches wits and swords with the evil Count Grendel - aided, of course, by Romana and the invaluable K9. |

Well-flowing swordsmanship by Tim Roll-Pickering 30/1/06

The back cover blurb implies that this story is driven by the quest for the Key to Time. But if anything, the quest is redundant to the story. Romana finds the segment early on and even Grendel and Lamia taking the crystal segment to examine it makes no impact on the plot at all. The monster is disposed of quickly as well and we are left with a fast-paced tale of dual and duality. On television The Androids of Tara worked as a fast-moving costume piece, with the technology slipped discretely into the story but never dominating it (despite the title). For the novelisation Terrance Dicks has managed to retain much of this dynamism, making events more at a rapid pace and rarely stopping to let the reader wonder about matters such as how the android technology arose on Tara, given that everything else appears so primitive or why the rulers are prepared to allow peasants a monopoly on android building and repairing without the risk of the feudal infrastructure collapsing either through revolution or the development of capitalism. Instead we get a tale of swordsmanship, in which the Doctor is forced to help Reynart secure his throne.

Normally a novelisation offers the opportunity to tighten up the plot, explain onscreen inconsistencies or brush over dodgy special effects, but there are few problems with the script of Tara whilst the BBC's reputation for costume drama and the limited effects meaning there is little need for enhancements here. The Taran beast is however described better than it looks onscreen, being portrayed as looking like a cross between several animals, but it still remains a redundant element in the story that merely serves to show that it is not necessary to have a monster in every tale. The other element that has been changed is the degree of humour, with the character of Farrah no longer sent up so heavily. Humour is difficult to pull off in print, especially when adapting someone else's original material, and so Dicks wisely sticks to a straight rendition of the story rather than risk it degenerating into a turgid jokefest that goes nowhere.

One character who comes across stronger here than onscreen is Lamia. Her desire to marry Grendel is emphasised heavily, as are the social barriers against it, but midway through the story it does start to feel as though she has a chance. But then she gets killed for no reason other than being caught in crossfire whilst serving her master. There is a real sense of tragedy here even though her death is only briefly dwelt on.

In a period when the Target novelisations were feeling more and more like machine products, it's good to see an adaptation that whilst sticking to the televised story does nevertheless manage to make it work well and fast as a novelisation. This is one of the best of the "Bronze Age" books. 6/10

The Romance of Crime by Jason A. Miller 1/7/21

The Androids of Tara is a very subtle story, and something very rare in mid-1970s Doctor Who. It's a story with only light sci-fi elements; it's a Key to Time story in which the hunt for the Key is a complete non-factor; and it's a story that's more about sex than any other Doctor Who story since The Romans. The basic plot is "about" a dim-witted Prince and a scheming Count jockeying for both the throne of the planet Tara and the hand of the Princess, but there are androids and laser swords to make it (nominally) a Doctor Who story. And it's tremendously witty, with one of the few villains in Doctor Who who's acknowledged to have had sex with another character ("I once showed her a certain courtesy").

So how do you take all that swashbuckling and romance and sin, and boil it down to a 110-page Terrance Dicks novelization? In 1980, a year in which he wrote ten books in twelve months, Dicks had a pretty pat formula down, but an atypical, clever and subtle story like Tara wouldn't seem to fit neatly into that formula, would it?

And, as is usual for Dicks in 1980, he doesn't have much space to embellish the story itself. So he doesn't add backstory to the Taran characters, other than what was already embedded in David Fisher's dialogue. Fisher himself later wrote his own novelization of The Androids of Tara, available only as an audio release, which filled in Taran history, but that was in perhaps excessive detail, turning the tale more into parody than homage.

But where Dicks makes his living is in the margins of the story. He's has a limited page count, so can't embellish much, and he's primarily transcribing the camera scripts, and therefore doesn't have access to all the mid-rehearsal changes and Tom Baker in-studio ad libs (so we're missing "My hat is on fire" here, as well as Count Grendel's TV parting shot, "Next time I shall not be so lenient!"). Certain effects look different on the page (the Taran Beast is "a good eight feet tall", and here Romana and her doppleganger Princess Strella are not fully identical). Dicks instead brings those camera scripts to life by commenting giddily on the action, telling us what characters were really thinking, papering over plot holes or budget-saving necessities (Tara, populated here by about nine speaking roles, has a "curiously deserted feeling"). Even better, he adds a hefty Marx Brothers-level of riffing on the script; just as Groucho Marx could never let a straight line go by without turning it into a pun, so too does Dicks fill the page count with relentless observations, sarcastic comments about the villains or wry humor. A typical three-paragraph sequence goes like this: Dialogue, stage direction, Dicks pun; dialogue, stage direction, Dicks insight; dialogue, stage direction, joke.

As far as Dicks' opening sentences go, this is not one of the all-time greats, and doesn't exactly set the tone: "The Doctor was playing chess with K9". Like the Key to Time itself, this chess game has nothing to do with the plot of The Androids of Tara; it's a filler scene. But Dicks does use the TARDIS scene to work in a rare continuity reference to another era, as the Doctor finds a Martian sonic cannon somewhere in a TARDIS cupboard. Dicks also defines Izaak Walton as "the great fishing writer", which is a help to those of us pre-Wikipedia who'd never heard of Walton.

Dicks does a fine job writing for Mary Tamm's Romana, who in Chapter 1 alone shoots the Doctor a "withering" look and reflects on how she wants to avoid "those ridiculous irrelevant adventures he always got mixed up in". Dicks also mocks the deus ex machina that is K9: "He had a surprising range of abilities, but swimming wasn't one of them".

The page count doesn't permit long introductions to each character, so Dicks has to economize, by describing characters in the sharpest possible way, using the minimum amount of words. Prince Reynart's chief swordsman, Zadek, "had the harsh, stern voice of a man accustomed to command," and that's literally all we need to know. For Zadek's underling Farrah, one of the most one-note characters ever conceived for the small screen, drawing his sword is "his usual reaction to any new threat", which shows that Dicks grasped these characters' limited dimensions with keen precision. Madame Lamia (who received that certain courtesy from Count Grendel) "was strikingly attractive in an intense almost angry way", which defines Lois Baxter's performance with 99.8% accuracy. Dicks elaborates that Grendel and Lamia were obviously "more to each other than master and servant", and that in spite of her "fiercely independent spirit, Madame Lamia was frightened of the Count"; later on, Lamia is "burning with anger, but clearly too terrified to speak".

Sometimes, of course, Terrance gives a character more dignity than they deserved on TV. Tara's chief priest, the Archimandrite, is envisioned by Dicks as "a tough and wily old politician, with a strongly developed sense of survival". Quick, grab your pencil and sketch the Archimandrite just from those words alone -- you wound up with James Cosmo from Game of Thrones, right? ... nah, on TV, the Archimandrite was merely played by Cyril Shaps, who specialized in downtrodden shlubs, not cynical fixers. Princess Strella, on the other hand, "was a placid, rather dull girl", which seems unusually harsh, doesn't it?

Dicks can't spend too much time inside of Grendel's head -- we can't ever learn of Grendel's true feelings for Lamia, because this is a kids' book -- but there are some neat glimpses, such as when Lamia is killed by accident: "He looked down at the huddled form for a moment and drew a deep breath". Sometimes less is more, and you can imagine whole worlds of sentiment in Grendel's mind from just those words. Dicks also has Grendel speak "urbanely", which is a great word to put in a children's book. Romana later wonders if Grendel will have to kill the Archimandrite in order to cover up his crimes, which adds a nice little frisson to Grendel's villainy, not suggested on TV.

Without the benefit of Tom Baker's ad libs, Dicks still does a fine job of encapsulating Baker's anarchic, chaotic onscreen presence, as he observes, "Not only was the Doctor heading straight into danger - he actually seemed to be looking forward to it". Romana later wonders "if for once the Doctor had over-reached himself" by agreeing to swordfight Grendel, which suggests a vulnerability to the Doctor that Baker rarely strove to portray.

There are some dangling moments crying out for more elaboration which never comes, though. Lamia senses that the 4th segment of the Key to Time is part of something important, but this is never picked up again. We learn that Grendel's sergeant, Kurster, has carried out other murders for his master, but that revelation comes late in the day and is just crying out for any sort of illustration; Kurster in The Androids of Tara is even more one-dimensional than Farrah.

But at the end, Dicks has the Doctor pay tribute to Grendel's villainy: "He raised his blade in a swordsman's salute, with a kind of reluctant admiration for Count Grendel's consistency. All in all, he'd seldom met a more thoroughgoing villain in all his lives," which is a wonderful tribute from the author to the character (Dicks will not be saying these things about the inept villains in the next two Key to Time stories). At the end, the Doctor admires the "pleasingly romantic conclusion to the entire adventure".

You can tell when Dicks likes a story and when he doesn't. Even when he's dashing off a 110-page book in just three weeks. This one, it would seem, is one of his absolute favorites, and he doesn't waste a word.