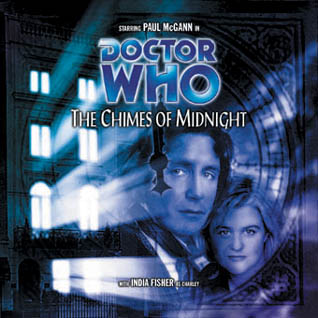

The Chimes of Midnight

|

|

Big Finish Productions The Chimes of Midnight |

|

| Written by | Robert Shearman |  |

| Format | Compact Disc | |

| Released | 2002 | |

| Continuity | After The Telemovie. |

| Starring Paul McGann and India Fisher |

| Also featuring Louise Rolfe, Lennox Greaves, Sue Wallace, Robert Curbishley, Juliet Warner |

| Synopsis: Tthe TARDIS places the Doctor and Charley into an Edwardian household, in 1906. There they meet the servants of Edward Grove who seems to keep his workers in a constant state of bewilderment and terror. When the scullery maid is found murdered, it falls to the famous amateur sleuth known as the Doctor to solve the mysteries. The only trouble is, the household keep shifting into different moments in time. |

"It Wouldn't Be Entertaining Without One of Mrs. Baddeley's Plum Puddings" by Peter Niemeyer 6/4/02

I enjoyed The Chimes of Midnight immensely. For all the McGann audios, I listen to one and only one part per week. This serial really had me looking forward to the next part days before I actually listened to it.

The best part of the audio was the mystery itself. I knew absolutely nothing about the story prior to listening to it, and I'm glad I was so ignorant. During part one, I though it was one kind of story. Part two made me think it was something else, and this shifted again in part three. I'm starting to find that the less I know about a story, the greater the likelihood that I'll enjoy it.

I really enjoyed the Doctor. He comments early on that he feels his previous incarnations have been too intentional in their travels...setting coordinates and visiting places intentionally. He wants to just go where the fates will take him. In one of the earlier audios, he comments that he just can't muster the effort to pretend he's someone he's not. I like all of this. With every passing incarnation, it can be harder to make a new Doctor stand out from the ever-growing pack. But I feel McGann's Doctor has been doing this nicely. Charley also gets a lot to do. I like it when a companion's role is pivotal to the story, and it was good to hear discussion of something she experienced in an adventure previous to this one.

I was also entertained by the dialog. At first, I was annoyed by the "Christmas wouldn't be Christmas without..." comment, but I changed my mind when I began to see how this, and other similar comments, were really part of what was going on. And Mary's comment about the Chrysler (or Bentley) was priceless.

(This paragraph is a bit oblique to avoid revealing too much to those who haven't listened to it.) The only down-side was the resolution in part four. The first three parts built a very entertaining conundrum, but I didn't feel part four fully lived up to it. The climax involves Edith's choice to be < x > or < y >, but wasn't she already < x > at that point? That was the whole reason the Doctor made his "gentlemen's request" to Shaughnessy, right? And if she was < x >, how could she decide to become < x > again? And why did the whole business occur in 1906? Edward Grove says this is where the whole thing was started, but how? If the Doctor and Charley hadn't intervened, what pivotal event in 1906 would have occurred?

But, all in all, money well spent. In my mind, it's the most enjoyable McGann CD so far.

Arc of Enjoyment (Part-by-part ratings from 0 to 10): 9-9-9-8

A Review by Richard Radcliffe 16/4/02

I have never (and I really mean never) looked forward to a DW product with quite as much enthusiasm as I did with this. After the excellent Holy Terror, Rob Shearman's name alone made it a must-have. But that wanting was doubled when the subject matter was announced. An old house in the early years of the 20th Century. The promise of a Sapphire and Steel mystery, where the lights turned down was absolutely essential. When it finally arrived (on the day of release thanks to Big Finish Subs) I had to listen to the first 2 parts that very evening. I was determined though, to give the story the full effect. 2 dark evenings I would give it, 2 episodes on each evening (4 is just too much at once, even for the best stories).

The opening episode is perfect in establishing the main characters. Like the board game Cluedo (that this story reminds of a great deal) it has 8 key players, 1 of which is definitely the house itself. In this murder mystery though there is no Mr Black, you don't know at first who is going to get killed. The 7 Colours on the Cluedo board don't have an obvious star either - this one has the Doctor.

Paul McGann is everywhere in this story. The limited setting of the house provide us with a Doctor-centric tale - and McGann is superbly up to the job. The servants see him as a great Detective, but the Doctor knows this is not your typical whodunnit. The 8th Doctor displays an infectious enthusiasm throughout to get to the root of the problem - one that he is particularly qualified to sort out. The 8th Doctor has never been this good, in any medium, this could well be the definitive 8th Doctor story.

India Fisher revels too in the close confines of the plot. She seems more "involved" in proceedings than the Doctor, and Charley's uncertainties about what is real and what is not, is well played. Charley has always been a great companion for the Doctor, but when she comes into the limelight (particularly the final episode) she really shines. This story adds much to a character that is quickly becoming one of the best there has been. The 8th Doctor and Charley have been good before, but never this riproaringly brilliant.

The 5 servants that populate the house are familiar. We've seen them before in this Edwardian House setting. Butler, Cook, Scullery Maid, Chauffeur, Lady's Maid - they're all here. Their limited repertoire strengthens their stereotypes, but it's all part of the greater mystery. The best character, apart from the Doctor, is the House itself. Marvellously brought to life by writer, director and sound technician. It always seems alive, right from the word go, and as the story progresses so its true nature is revealed brick by brick.

The characters, house included, make the story. They provide the build up of tension, the intrigue, the mystery and the laughs. There are plenty of fun lines, which the author repeats to maximum effect - Plum Pudding at Christmas being the most smile-worthy. Rob Shearman has produced another brilliant script, that glories in atmosphere and mystery. Big Finish thrive on such material, and give the whole production a massive boost as always. The eerie ghostlike noises, the creaking doors, the ticking clock, the melancholy musical accompaniment - it's all here and the effect is genuinely eerie and spooky. This really is a story that demands you listen to it with just a small candle for company on a dark, stormy night.

The story is a mixture of horror, fantasy and sci-fi. Rob Shearman establishes the characters and setting, lets them run for a bit in Episode 2 and 3, and then pulls off a stunning climax as the answers are revealed. It's quite a feat to embrace so many "types" in one single story. That it emerges from its inspirations and clear source material as a marvelous work in its own right, and very much a Doctor Who story, says everything about the author's skills.

It makes you jump, it brings out the goosebumps, it makes you wonder and marvel. Above all it makes you glad that you're a fan, and your allegiance to the good Doctor has rewarded you with this masterpiece. It is one of the greatest pleasures in life to want something, to eagerly anticipate it. To then finally have the prize and find the reality is even better than the dream is even more wonderful. I cannot think of a Doctor Who story that has entranced and enthralled me more. 10/10

The best yet! by Joe Ford 22/4/02

I have noticed a little pattern. Are BBC books and Big Finish in collaboration or something? It's just first we get a comedy double bill poking fun at the series (Mad Dogs and Englishmen and The One Doctor) and now we have a horror double bill involving time in a big way (Anachrophobia and this wonderful CD). Just thought I'd mention that.

I won't mince words (which makes a change) this is the best CD Big Finish have released surpassing even The Holy Terror, Shearman's last masterpiece. And why is it so good, let me tell you…

Supplement, 1/10/04:

It is rare for Big Finish to get a production this right. As far as I am concerned this four episodes of pure heaven, appealing to the old school fan in me who likes to be scared shitless and the freshman fan in me who enjoys seeing the companion being far more vital to the plot than I am used to. There are a number of superb elements that combine to make this story so special, not least the superb writing and performances (which I shall go into later) but there is one thing that is rarely mentioned that I think gives this story an atmospheric edge other all the others...

It's a haunting Christmas story and if there is one thing I LOVE it is a really scary Christmas tale. Before you even have to work on the mood and music to inject fear into the listener the sheer fact that it takes place of the Xmas season, with lots of references to crackers, sherry, plum pudding, roaring fires, biting snow, etc, allows the listener to capture the spirit of the story so easily. One scene sees a conversation between Charley and Edith with a discordant humming of Hark the Herald in the background and it is wonderfully creepy. I adored the Doctor's charming reaction to the time of the year and the constant black humour surrounding the bizarre deaths occurring at the worst time of the year... just who will serve the masters upstairs if the staff keep popping their clogs at Christmas?

Rob Shearman has constructed an ingenious script, written in a supposedly bad period of his life (although I always find I am at my most creative when I am depressed, funny that...) and one that provides Paul McGann with his first uber-classic (the other being Scherzo from season three), a story that stands out from the crowd because it provokes a startling emotional reaction but also leaves you in a tizzy at how devilishly clever the whole thing is. By centering the story around Charley and her survival from the R-101 it manages to tie in beautifully with the running arc and yet tell a discreet standalone tale that doesn't affect the rest of the year and the other side effects of her survival one iota.

I won't pretend to be half as clever as that brainy git Rob Matthews and write a dense essay on the story but I will do my best to explain just why the story affected me so strongly. How it highlights the staff below stairs in life is extraordinary and Rob says something very special about all people who don't make the important decisions that shape the world, about those who spend their entire lives giving and giving and never getting anything back for it. These people are just as important as anyone, without them there would be a gaping hole in society that would have to be filled. But the story unflinchingly reveals how trodden upon some people can be, like Edith, constantly told they are worthless and wont amount to anything... what I fear Shaugnessey and Mrs Baddeley fear is that Edith has genuine potential and could surpass them if she wasn't kept in her place. The fact that a mere smile from Charley was enough to affect Edith so much as to create the entire paradox the brings Edward Grove alive, that she could experience such joy from such a small gesture is a healthy reminder that we should respect and appreciate those around us, even if we are in what society deems as a superior position. Like all of us Edith has hopes and dreams and thoughts of love and happiness, it is the fact that none of these are fulfilled that makes the story such a tragedy. The story finishes on a heartwarming note as Edith realizes that her actions, just being herself, is enough so that Charley will remember her forever. As she says so eloquently "However lonely I might get, I'll still make a difference!"

It is that intimate 'downstairs' atmosphere that gives the story such a strangling sense of claustrophobia. Even before we get into all the temporal trickery and scare tactics it is clear that these five people have their own little world below decks, relationships that provoke strong feelings and a hectic life of never-ending work in just a few tiny rooms. It is only when two outsiders, the Doctor and Charley enter their world that things start to go very, very wrong...

I have heard people bemoan the Doctor and Charley relationship in recent months and to be fair their friendship has shown signs of running out of steam in the latter third season stories but here in the early stages of season two they were at the top of their game and in The Chimes of Midnight we see the ultimate expression of the strength they bring to Doctor Who.

Paul McGann has never been better and it comes as no surprise to hear it is one of his favourite stories. It is rare for the eighth Doctor to be scripted so vividly and his character is truly put through the wringer in this one. He has loads of brilliant lines, especially as he starts to enjoy himself in the Hercule Poirot role of discovering who is the murderer below stairs. Subverting Doctor Who stereotypes he immediately admits that two strangers turning up when a dead body is discovered is suspicious indeed, only to be told to his utmost surprise that the staff would never dream of accusing such respected members of society! As the bizarre deaths pile up, sink plunger asphyxiation, plum pudding stuffing, sink water drowning, car squashing... the staff continue to opt for suicide and the Doctor hilariously disproves their claims. It is only when the game starts to turn against them that he grows concerned, as they start to discover the truth the killer starts to draw Charley away from him and he has to really fight to win her back.

The eighth Doctor has always been the most vulnerable of incarnations but here he trades that image and becomes the master manipulator, in the dark about who the killer is but aware of how to draw him out of hiding. When he realizes that it is the house that has been running the game he demands a face to face confrontation which leads to one of the best ever scenes of its kind as he questions its existence as worthwhile and pleads for it to commit suicide. He realizes he will be trapped forever if he doesn't get through to the house and that he will lose Charley and in a final act of self sacrifice offers himself as a victim so he can beg Charley to not kill herself...

Wowza! India Fisher is one hell of a performer and no mistake! She takes Charley to such heights in this story, playing a number of very difficult emotions to capture on audio only. It is rare to see such a raw, personal performance in Big Finish, I think only Maggie Stables and Colin Baker have managed it as well India does here, taking Charley into the depths of hell and back. We learn quite a bit about Charley in this story, about her lifestyle back in the 1930's. Her aristocratic personality lends her an arrogant air but her desperation to help poor Edith in the latter episodes reveals what a thoughtful and caring woman she really is. It is easy to sympathise with Charley's situation, early episodes suggesting someone is rummaging around in her memories and the later ones proving she should have never survived the crash at all. Having her confront the lingering doubts in her mind is a good of getting close to her and as she has to witness what 'would' have been her death it is heartbreaking to see her breakdown and admit she doesn't deserve to live. Leaving the twist that she is responsible for the entire story so late is a wise move and provides the story with a touching climax as the Doctor steps in and convinces her that he needs her and she HAS to survive.

The other characters are just as well drawn, despite the lack of continuity as the timeloop plays out over and over again. It is easy to get to know the characters with their amusing phrases ("I'd say Mrs Baddeley... she's got shifty eyes!", "Christmas wouldn't be Christmas without your plum pudding Mrs Baddeley! It just wouldn't be Christmas!", "I'm sure we can conclude Doctor that it was suicide!")... indeed the dialogue throughout is as sharp as Doctor Who has ever been, at times grotesquely comical and at others astonishingly thoughtful.

Of course the story belongs to Edith, the scullery maid who was abused and ignored her whole life to the point of being forgotten entirely after her death. She remains as compelling character throughout, both in her naive younger guise and her bitter, older guise. Despite rare moments of kindness such as the butler writing her name in the dust or the chauffeur knocking her off, there is little but contempt for her and it is easy to be drawn to somebody who is so unfairly dismissed. The pinnacle of her story and the point in the story that I had goosebumps running all down my arms was when she reveals her suicide, hearing the news of Charley's death and coming down in the kitchen and taking a knife to her wrist... it is enough to make you weep to think she could commit such an atrocious act because Charley was the one person who showed the slightest bit of kindness. The clues of this revelation are cleverly integrated into the story, especially the blood curdling scream and the cryptic statement "Edward Grove is alive... together we make him so..." How Edith forces Charley to make a decision, either she lived after the crash and her suicide was unnecessary or she died and it was for the right cause, is gripping... as the two of them stand there on the edge of insanity, the knife between them, deciding how history should play out and Edward Grove's fate.

It is the incidentals that make the story so special and in the first few seconds you can hear that this is going to be lavished with far more care than usual. Barnaby Edwards shows the lightweights around him how these Big Finish plays should be directed properly, with heavy music cues providing plenty of atmosphere and emotion and disturbing sound effects that will chill your bones. I listened to this in the dark the first time I heard it and I almost shat myself on several occasions... and when Edward Grove throws up some maniacal laughter I had to switch my bedside lamp on! Russell Stone's music pushes the tale along effortlessly and is never intrusive and yet provides some excellent chills... I love the discordant horn everytime the Doctor realises they are being manipulated and the exciting tingle as time is raced forwards towards another murder. The piano is used wonderfully in the last episode in the scenes between Charley and Edith and a spine chilling wind instrument floating in the background.

The performances are superb and it sounds as if this crew have been working together for years rather than just meeting up for one weekend. There is a pleasant mix of accents and ages too which helps in the early scenes to figure out who is who.

There are even three classic cliff-hangers that leave you desperate to continue the story, the first terrifyingly scary, the second unbearably exciting and third almost impossible to believe. If only all Doctor Who writers could get this staple ingredient so right.

What more is there to say, a story that hits on every conceivable level, like Camera Obscura for the book range or Talons of Weng-Chiang on the telly, a story that is so perfect you have to wonder how they don't manage it so often. This one was so good even Simon was gripped throughout and he doesn't get on at all with audio.

Don't Mention The Penguin!!!!!!! by Robert Thomas 16/5/02

The second story into the season and things are definitely hotting up, after the 'romp' that was Invaders From Mars things start to get serious in Chimes. The seriousness is treated by all from the writing, to the acting to everything else. As well as being serious Big Finish have this time gone for a spooky and claustrophobic vibe. The power of this story is in its characters and setting, managing to evoke many a good scene. This story manages to surprise a bit because after part 1 I was enjoying it but wasn't sure if they could get another three episodes out of it.

Amazingly they did and they were very different from the first part. In fact I'd say that the two middle parts are far superior than those which surround them. These two parts have certain scenes where characters heads are really f**ked with and are some of the strongest produced so far by Big Finish. In saying this the cliffhanger of part three is one of the best yet.

As for the acting the regulars are as good as ever, this team is fast becoming a personal favorite. Paul McGann is brilliant as his character changes throughout at first behaving as though he's having fun until he realizes how serious the situation is. India Fisher appears to be enjoying the focus that this season is putting on her and continues to excel. The guest cast are mostly good, I'll specifically single out Lennox Greaves and Juliet Warner, on the other hand Louise Rolfe is very poor which is disappointing when she is such a pivotal character.

This story is definitely something to shout about but for me it is let down towards the resolution. I've mentioned elsewhere that in Space Age Steve Lyons doesn't appear to know what a Mod is, here it looks as though Rob Shearman has mixed up the notion tough luck with a certain word beginning with 'P.' It doesn't take the quality away from the story but however it does make the revelations and conclusion very frustrating. Although it may be settled by the end of the season depending which way the future stories go.

The Chimes of Magic by Julian Shortman Updated 20/3/03

Listening to The Chimes of Midnight reminds me of a card trick that I used to perform when I was younger. It was one of those traditional ‘pick any card from the pack and (after several elaborate stages) I’ll discover the one you chose’. The trick involved asking the participant to decide which cards should be discarded. The piles would become smaller and smaller, until only one card remained - the card they’d originally chosen. They key to pulling off this trick was to lead the person to believe that they had decided which cards should be discarded - where as of course, I was manipulating their choices all the way.

In The Chimes of Midnight, Robert Shearman leads the listener through a series of intriguing questions. As the story progresses, ‘answers’ are gently dropped into place, until by the end, we’re lead to believe that the whole picture has been revealed. On the first listen I was taken in, almost hook, line and sinker. But something niggled in my mind which caused me to ponder the storyline again, at which point I realised I’d been skilfully duped. The questions had all been answered, but not all of the answers made sense – it felt a bit like being given all the pieces to the puzzle, only to discover that they didn’t all fit together.

This illusion of being given the whole picture was often achieved in the story by using the Doctor’s outbursts of childish enthusiasm as he discovered the ‘answers’. In many DW stories, the Doctor’s explanations are trustworthy keys for the listener to understand the mysteries, and the more confidence he delivers them with, the more likely it is that they’ll turn out to be correct. A prime example of this in The Chimes of Midnight is when the Doctor exclaims his realisation as to why the house can only influence events as the grandfather clock is striking the hours. It sounds convincing at the time, but on reflection, I don’t think the explanation hangs together well.

Another ploy used to dupe the listener was to suggest more than one plausible solution (often through a discussion between the Doctor and Charley) but then avoid confirming which ideas were the real ‘answers’. A good example of this were the ideas suggested to answer the mystery of the existence of the servants (apart from Edith). The idea that they might only be representations of Edith’s past & future was plausible (and interesting), but that didn’t tie in later with the final happy scenes where everything was ‘back to normal’. If they never were part of the normal universe, surely they’d have ceased to exist when the paradox was resolved?

Ah, yes, the paradox. Now this was a clever and rather nifty idea – although I suspect some newcomers to BF’s McGann adventures might feel a little peeved if they haven’t heard Storm Warning. Again, on first impressions, the ‘answer’ to explain the time paradox seems reasonable – if someone kills themselves because they thought someone else was dead, but really that person is alive because they’ve cheated their fate with a time machine, a time paradox will ensue! But then again, maybe not? After all, isn’t there many a tragic tale of woe concerning people who’ve committed suicide because they believed someone was dead (Romeo and Juliet springs instantly to mind)? Edith didn’t commit suicide because Charley was dead – she did it because she believed Charley was dead. So what difference does it make if she is still alive? Many a person has snuffed it in the course of history due to their misguided or misinformed beliefs concerning reality.

At this point, you could be forgiven for thinking that I’m on a mission to give The Chimes of Midnight a right slating. However, I think the important question to all the above rambling is – once you’ve seen the holes in the plot, does the whole thing fall apart at the seams to reveal an embarrassing lack of substance? On this occasion, I’m glad to say no. Many of the best ghost stories fall to pieces under close examination, and in some ways it’s an injustice to put them under the microscope – they weren’t created to be dissected piece by piece. They were created to scary the willies out of us. The Chimes of Midnight sets up the illusion of a complete story – and if you’re someone who’s happy to hang your rationale up at the door when you put on your headphones, you’re in for a great ride. It has chilling moments a plenty, and enough fodder to fuel nightmares about being trapped in haunted houses.

I’ve listened to this story again since I picked it apart, and I’ve still been chilled by Edith’s ghostly warnings, the hands of the watch spinning round, and Charley’s regression whilst eating plum pudding. You see the scary concepts are still great, even if the ‘answers’ don’t hold water tightly. The attempt to provide ‘answers’ feels like a nod towards satisfying the rational side of DW, but it doesn’t really matter that some of them are hogwash – the creepiness more than makes up for it. And to be fair, one ‘answer’ which did hold together well was the developing ‘life’ of the house. I thought it was a fantastic idea (and original in DW) to have a building slowly developing a personality of its own as it fed off the traumas of its inhabitants.

As for the actors, McGann and India Fisher were on top form throughout this story – McGann’s portrayal of the Doctor continues to feel fresh, and I relish hearing each new adventure with him at the helm. It only continues to show what a shame it is that he never got a decent run at the part on TV – but thank BF that we’re getting a sizeable helping now. These adventures are the nearest I’ve felt to getting brand new Who since 1989, and it’s stoked up a fire of enthusiasm about DW which had all but died in the early 90’s. Credit should also go to Lennox Greaves for his excellent performance as Shaughnessy – the part where he confesses his despair about losing control to the Doctor I thought was particularly strong.

Finally, a nod of thanks to BF for finally getting Charley on the front cover of a release – considering the pivotal role she played in this story, it would’ve been a crime not to, and it continues please me to see covers that look less like DW image archive composites, and more like original designs.

A Review by Stuart Gutteridge 23/8/02

Due largely to it`s atmosphere, The Chimes Of Midnight proves itself to be an enchanting and endearing tale. Paul McGann`s Doctor has rarely been better, treating things like an adventure to begin with and becoming more serious as events take a darker turn. India Fisher also revels as Charley, as she is given more depth than ever before. This story has been described as a mixture of Upstairs Downstairs and Sapphire And Steel, and it isn`t hard to see why. Christmas also works in the story`s favour, adding much to the overall feel of the story and this is reflected in the supporting cast particularly Louise Rolfe as the downtrodden Edith. Add to this subtle touches, such as the clock ticking and you have as near perfect Doctor Who as you`re ever likely to get.

A Review by John Seavey 10/5/04

Wow. Wow. Wow. Bloody brilliant. Better than sex. (It certainly lasts longer, at least.) Rob Shearman is a god among men, writing a wonderfully creepy, delightfully funny, utterly spooky ghost story that remains solidly grounded in Doctor Who. Every moment of this is a gem when you're just reading the bloody script (in The Audio Scripts, Volume Three), and every performer and all of the production people just add to the lustre of what has to be one of the most sparkling gems in the Big Finish crown.

In case I'm not being clear enough, this is an absolutely amazing audio play, and a delight to listen to. If you've not heard it yet, go find a copy and give it a listen now.

A veritable accomplishment! by Rob Mattthews 17/6/04

On the strength of Jubilee, The Holy Terror and this here audio adventure - and notwithstanding the misfire that was Deadline -, I must say the one thing I'm particularly looking forward to about the new TV Who series is Robert Shearman's contribution. I've listened to four of his Big Finish stories now, The Chimes of Midnight being my most recent foray, and there's no doubt in my mind he's one of the best, most uniquely recognisable writers ever to be involved with the property.

On the evidence thus far, too, he appears to belong to a particular breed of artist that really interests me, the kind who basically creates the same text over and over. Not in a negative or self-plagiaristic sense, mind you - I mean it very much as a compliment, analogous to the way Hitchcock made pretty much the same three movies over and over, Hopper painted pretty much the same three pictures over and over, or Robert Holmes wrote pretty much the same three or four Doctor Who scripts over and over. What's interesting about similiar stories is not the similiarity itself but the scope for endless variation on a core idea, and I really like artists who've zeroed in on their own distinct collection of ideas and motifs and can spend careers exploring them in numerous recombinations. It speaks of real passion and genuine talent, to my way of thinking.

So partly I'm looking at this as a representative example of Shearman's Who work, because - as is always the case with that kind of artist - the overt resemblances between those works actively invite comparison. But I ought to make it clear upfront that, all on its own, Chimes of Midnight is a fantastic, funny, shocking, entertaining and moving story, and that if you never listen to any of Shearman's other plays it won't affect your enjoyment one iota. Also that the acting is top-notch all round, and I'm probably going to unfairly neglect that factor here... Let's just say both regulars and the guest cast shine throughout, and India Fisher impresses me more and more as Charley with every story I hear. It just so happens, though, that in explaining the appeal of this story, I also find myself explaining the appeal of this Shearman fella's writing in general, so I'll focus on that a bit.

There are spoilers here, obviously. If you haven't heard the story and just want to know if its worth buying, then YES!! it is, it's excellent. You really should have gathered that from the above reviews. Run out now and buy it. Have a listen, and then read on...

Shearman comments in the liner notes that Chimes developed from an idea for a Christmas-themed murder story, and mentions that he toyed with the notion of dubbing it The Holly Terror. He's joking (I think!), but actually that would have been quite appropriate, since the similiarities between the two plays are so striking that Chimes almost feels like a several-generations-down-the-line remake: the story involves a basic scenario being mysteriously played over and over with random variations within an enclosed, classically spooky environment which no-one is able to leave (in Holy Terror the endless varied 'replays' were suggested, rather than experienced directly by the listener as they are here), both stories have a cast of oddly two-dimensional stock-type characters who are ultimately revealed as facets of a single, emotionally tortured human being, and both stories have the Doctor and his companion being 'written into' the scenario - written in within the world of the story itself - upon arrival. And in both stories, as in Jubilee also, the TARDIS plays an unusually pivotal role.

Beyond those specifics, all three of these stories have major similiarities both structurally and in terms of tone. The situations and environments of these plays are determinedly self-referential in a way that, compared to many a Doctor Who story, could appear incredibly convoluted - none of them take place in an everyday 'real' world with a background hum of its own, rather each takes place in some kind of enclosed situational nexus - like Jubilee, Chimes is founded not on a naturalistic situation, but on a paradox. It's not about walking into a situation where a big 'something' then happens, rather the situation is a refraction of the big something. In this case it's a kind of postmodern potboiler erected around the anguished interior life of poor Edith Thompson

On paper, the catalytst-paradox idea of Chimes would probably seem pretty abstract and dryly intellectual. You can imagine its not really coming alive in the hands of a lesser writer. And yet... 'alive' is one of the most apt words I can think of to describe Shearman's writing. It veritably pulsates with energy like a... veritable pulsing thing. As Mrs Baddeley might say.

Despite their ornate structure, these are some of the most deeply, seethingly human Doctor Who stories I know - because in each case the dementedly over-ordered logic of the story flowers around the pure, naked feelings of a single human being - like the man who murdered his son in The Holy Terror, and to a less prominent extent Rochester in Jubilee... and of course here in The Chimes of Midnight, Edith Thompson. Few Doctor Who stories have so furiously solipsistic a focus, an instinctive grip on the plain, untempered emotion of a single person. Here, as in The Holy Terror, that emotion both creates the outward scenario and ultimately overrides it.

The moment you first hear the ominous phrase "I am nothing, I'm nobody' in Chimes, you know in your gut you've just heard the key to what the story is about, you just don't yet know why. That's to do with tone too, the sudden introduction of a jarring note of cruelty and a buried cry of despair in what appears a lightly comical scene. The pure unfettered emotion of the individual is given primacy over the societal structures designed to contain the individual - Mike Morris noted the same of The Holy Terror -, and the sense of discord between the two is the more strongly evoked because of the absence of a well-adjusted emotional middle-ground, as there would be in a more expansive drama of the everyday. Here there's Edith the person and Edith the 'component' of the house - and the greater social order - and never the twain shall meet. Even the emotional connections poor Edith does manage - such as relationships with people like the chauffeur Frederick - can be effaced, made to not exist by a renewed affirmation, on their part, of her lowly status - a chauffeur having an affair with a scullery maid is unthinkable, therefore it can't have happened - a convenient ideology for those on the higher rungs of the social ladder (reminds me of Tommy B's 'The very stupid and the very powerful' line in The Face of Evil), and a completely suffocating one for those at the bottom. Edith's situation breeds bitterness and rage. And here the primacy of that pain actually 'bleeds' into the plotting logic of the story itself, corrupting it - on my very first listen I smelled the rat with the explanation for the paradox, namely that there's actually no 'technical' reason for a paradox to occur at all.

A previous reviewer has commented on this - the basic error being that Edith didn't die in fact because Charlie did, instead she died because she thought Charlie did, hence there's no contradiction and no paradox. But you can't really bring yourself to feel that this invalidates the story. Shearman creates his paradox from the phantasmic logic of feeling rather than the strict nut-and-bolt logic of sci-fi, or even bog-standard rationalism. Not that I'm suggesting he made a plotting mistake on purpose, rather I'd imagine that he was blinded by his more expressionistic concerns, basically that, whatever the original inception, he - that is to say his writing - cared more about the story of Edith.

I think imaginative empathy is a major strength of this writer. His stories are all in a way about, dammit, bothering to care. I doubt Robert Shearman has ever been a scullery maid, but damned if his writing doesn't put itself fully in those shoes.

But what makes his work so very entertaining and engaging, what makes you want to stick with it, is not the eventual emotional punch - because after all, like a twist in a movie we don't know ahead of time what that's going to be -, but Shearman's distinctive hook: his sense of humour. And it's really his aptitude for black comedy which makes his approach to Doctor Who writing unique. It is in a way the defining quality of his his work, the default tone of these three plays being a rabid mating of horror with comedy, the two at it like rabbits behind the back of their more staid and respectable partners, 'straight' drama and tragedy, feverishly spawning those jarring notes, like that mentioned above, which suddenly change the feel of a scene entirely, wrongfooting us.

Shearman is actually, so far as I can recall, the first writer to not merely attempt, but successfully establish 'the Doctor Who black comedy'. Hints of it reared their head on TV from season 22 onwards - if you look at Vengeance on Varos, The Two Doctors and Revelation of the Daleks they all have bits designed to provoke uneasy chuckles amidst revulsion, and Ghost Light makes several overtures in a grotesquely humorous direction, but by comparison with Shearman's work the attempts made in those stories are all relatively tentative and experimental.

I think where Shearman has succeeded is in managing to fuse the values of black comedy and those of Doctor Who without losing what makes either of them so special. And when you start to think about it, the values (such as they are) of black comedy would seem to be anathema to the strong moral values of Doctor Who, which to me makes the fusion all the more impressive.

So, forgive me if I now rant for a bit ('Oh Christ, no!!!' I hear you yell) on my idea of what black comedy is, and what makes it so good when it works. I just need to establish that before I get to Shearman's Doctor Who 'twist' on it:

Okay, I've thought for ages that there's a strangely close relationship between comedy and horror. Typically when I try to expound this theory in conversation it just earns me puzzled looks, but undeterred I go on to insist that, when you think about it, both forms are at root about the very worst thing happening that can happen - they are, to differing extents, about the frustration of hopes or expectations, about things going badly tits up.

Course, this little theory of mine has always been just a sitting-in-front-of-the-TV talking-rubbish kind of opinion, not thought through in that much depth. I admit that on reflection neither comedy nor horror can really be discussed as broadly as all that - there's a world of difference between Val Lewton's I Walked With a Zombie and George Romero's Night of the Living Dead, for example, even though they both count as horror movies about zombies. And, fishing around in the comedy area, I do recall that, um... well, the Marx Brothers didn't rely on misfortune as a major component of their schtick. I can't think of any other examples, but perhaps that's down to the vagaries of my own tastes.

Nevertheless, and even if I am only going by things that I like, I think it's fair to say that the tits-up factor plays a prominent role in a large swathe of twentieth, not to say twenty-first-century popular comedy - if you look at Laurel and Hardy for example, or Fawlty Towers, or Seinfeld, or more recently Alan Partridge and The Office; all are very different but each of them is in a very fundamental way about the hopes of their characters being cruelly, excessively, dashed (to varying degrees of poetic justice - Stan and Ollie rarely deserve their fates, for example, whereas George, Jerry and Elaine usually do). And you can see a similiar phenomenon if you look at various horror films of different sorts too - The Shining, in which Shelley Duval accompanies her writer husband on a kind of working holiday and end up being chased around a haunted hotel with an axe; Psycho, in which poor Marion Crane checks into a dodgy motel and ends up with half her innards down the plughole; Suspiria, in which a ballet school turns out to be a witches coven (admittedly the distinction is a fine one); The Blair Witch Project, in which a bunch of people go into the cinema expecting to be chilled and end up bored senseless... erm, I mean, in which a bunch of people go into the woods and, wouldn't you know it, can't find their bloody way out again. All prime 'Bugger!' situations - the Blair Witch scenario reminding you a bit of family camping trips -, but the difference perhaps being that things go even more spectacularly wrong in horror than in comedy.

One of the neatest navigations I've seen of the scrawny line between horror and comedy is the mid-sixties Hammer horror movie Dracula Prince of Darkness. The first forty minutes(ish) of that movie, before Christopher Lee turns up, is for me one of the finest examples of mounting suspense in cinema - in fact after Dracula finally turns up, the film just seems to meander for a bit, abruptly despatch the Count, and then finish. The first half is greatly superior to the latter. It's a situation that's rather familiar now - I think Eddie Izzard had the movie in mind when he incorporated it into his 'Agatha, Tabetha, Bagetha' standup routine; 'Four Victorians decide to go to Castle Dracula in Transylvania, for no reason at all...' -, but it's virtually archetypal; these four Victorians get chucked out of a coach by a driver who 'bain't gonna go no farther' and who 'don't see naw caarstle', they get picked up by some creepy horses that refuse to take them in the right direction, they end up in an overtly sinsister empty castle with their bags already installed in their rooms when they arrive, they have to sleep on lumpy matresses, and then finally end up as part of a sacrificial rite to restore the bloody Prince of Darkness, of all things, to life. In one way you could see that as the story of a terrible tragedy - in another, it's just another family holiday going really, really wrong. The plight of the two couples in the movie is genuinely tense and frightening, and yet also truly hilarious, because they keep politely refusing to see the obvious signs that something is up (except for the poor Barbara Shelley character, who's frightened out of her wits and whose misgivings are attributed to PMT or something). There's a scene where Dracula's butler (played by Phillip 'Borusa' Latham) dodders terrifyingly, protractedly out of the shadows, fixes poor Babs with a deathly malevolent rictus-fixed stare and causes her to scream her guts out... and then lightly mutters 'I'm sorry if I startled the young lady, sir'. It always makes me laugh out loud, but frightens me too, and I think it's to do with stepping back and forth across the line between putting yourself in the position of these people and just watching them on a screen.

Still, it seems to me that death is typically the cut-off point where things going wrong stops being funny. And yet this ain't so with black comedy, where things continue to be funny beyond death.

Black comedy, I guess you could say, sets out to mix feelings of amusement and abhorrence in its audience. That's an odd combination, because if you try as a bit of a thought-exercise (go on, you know you want to!) to posit the various dramatic genres as a continuum, decide where they stand in relation to each other, a 'classical' old-fashioned view would probably place a wide gap between them - comedy as a basically frivolous, un-serious form (frothy shite like Oliver Goldsmith, say), the rationale presumably being that giggliness doesn't go with godliness; next, drama as a more satisfying morality play form which invests its subjects with the same sense - and assumption - of dignity as is taken for granted by its spectators; then melodrama as an amped-up version of same, perhaps involving greater moral compromise on the part of its protagonists; and finally tragedy as a 'higher' form of drama, very simply drama with an unhappy ending rather than a happy one, an approach perhaps considered 'higher' because rather than providing reassurance it takes its exploration of what it is to be human to the very limit and does its damnedest to then step outside of that limit - a way of imaginatively testing our own limits, working out the points at which we ourselves would finally break - the dramatic climax of a tragedy being that truly unbearable moment when all human aspiration seems utterly negated - a kind of orgasm of misery if you like, like the horrific final tableau of Othello which must be covered by drapes because it 'poisons sight'. Tragedy, in a sense, makes the audience feel tough and ballsy because they're capable of facing it without flinching - a very blokey way of judging dramatic value, I think, though also a subconscious way of preparing oneself for when the shit comes down in your own life.

'Horror', surely, as a kind of grotesquely multiplied form of tragedy, would exist one step beyond this - seemingly at the very opposite remove from comedy.

But of course, the old-fashioned view I posit here would be misguided - certainly a current, postmodernist perspective wouldn't assume comedy to be an intrinsically 'lower' form than drama or tragedy - it'd be invited to prove its mettle and judged accordingly. My feeling is that generally you should approach analysis of a given text by the terms the text itself suggests. And when you remove the idea of comedy and horror existing on a scale of innate worth, you can see the anarchic, questioning nihilist spirit they share.

And what they share most, I think, or at least what comedy and horror of my suggested 'tits-up' variety, is a refusal to grant both characters and audience that basic illusion of innate dignity; a tragedy is only a tragedy because we feel we have something worth losing in the first place. But the suggestion that we don't have that can be experienced alternately as liberating or terrifying, depending on the context. When it's liberating and cathartic it's funny, and when it's scary and destablising it's horror. Both are animated by a basic unease taken to opposite extremes. Which is why black comedy done really well can be so much more vital than drama which occupies a safe emotional middleground. It's being pulled back and forth between two poles, hence its dynamism.

It's a dynamism which - now I come to think of it - has probably manifested only relatively in drama and fiction. There is, for example, no such thing as a 'black comedy' in the works of Shakespeare, at least that I can see (though there's perhaps a tiny seed of it with the porter scene in Macbeth), and since 'horror' itself seems only to have risen to prominence in the late nineteenth century (horrors contained in religious texts up until then, I guess), I wonder if there even was such a thing as black comedy before the twentieth century. I'm open to correction but it seems to me a uniquely modern, not to say Modernist, form. Not that I want to get back into the Modern/Postmodern debate in this here context. Better to say that I think it's developed thanks a fairly recent (ie - last hundred years-ish) mental shift in the way we view drama, due to factors like the two world wars and the development of a hardened metropolitan, urban attitude proliferated by increased forms of media like cinema. Thanks to the spread of the various media, and thanks to the wars of the twentieth century, we've become far more aware of the terrible things that can and do happen to people just like us, and horror doesn't seem so far fetched. A horror text, to my mind, is in a sense a kind of furious, sarcastic response to the cruel caprices of the world (what once would have been referred to as the Gods, or fate, or the immanent will) -, in the sense of 'You want tragedy? I'll show you bloody tragedy - here's tragedy times eleven shoved into a blender and served to your mother on toast!'. It's a kind of hysteric imagining of the worst that could happen.

About a week after the New York atrocities of 2001, that satirical goldmine The Onion (www.theonion.com) 'reported' the story with the headline 'American Life Turns Into Bad Jerry Bruckheimer Movie' - a blackly humorous joke, one which sort of 'got' me even though I couldn't bring myself to laugh, and in my opinion not a tasteless one. If anything, it's a reaction to the fact that the world itself can be so tasteless. It's a good example of black humour as 'sarcastic response to the heavens' I think.

Come to think of it, you can read any of Dave Stone's Doctor Who novels for several more - the Fourth Doctor blithely saying 'Skies black with the burning bodies of the dead are rather noticeable by their absence', or Romana shuddering at twentieth century Earth - 'All those extermination camps, it's so depressing' in Heart of TARDIS.

There's a line of 'ironic perspective' I think black comedy hops back and forth across - stepping back from the situation and thinking 'Oh God, that's such a ridiculously terrible situation you just have to laugh', or perhaps the giddily selfish response of 'hee hee, the bad luck's been doled out to them and not me', but then stepping imaginatively back into the situation and thinking 'Aargh shit, this is scary!' and jumping out of that place again. Then, because the text goes on, being drawn back into it again, getting freaked out and jumping out of it again, ad nauseum. I don't mean to suggest this is a conscious process, but I think we can distance ourselves from the characters in drama simply by choosing to remove our sense of empathy with them. In a way it's a cocktail of modern ironised viewpoint and old-fashioned suspension of disbelief. If we're presented with an absurd or dire situation we can recognise prompts as to whether to see it as funny and laugh, or see it as scary and be disturbed. When the situation involves death, the prompts to laugh are so shocking and transgressive they can in themselves provoke laughter. It's that successful to-ing and fro-ing which makes successful black comedies so vibrant - little wonder that there are so few successful black comedies (even The Simpsons has managed only one - the Frank Grimes episode!).

And so back to Robert Shearman, and Doctor Who (remember that? ... Hello? ... hello? hey, why's my voice echoing?). Okay, well the gist I've been trying to get across is that black comedy is anarchic and deeply anti-complacency (at its 'purest', it certainly has no truck with easy platitudes). That much it has in common with Doctor Who. Or the Doctor Who I like anyway - Pertwee's Doc rarely had a problem mouthing platitudes... However, black comedy is also about the undermining of our own feelings of dignity and worth, in a way about revelling in the worst that can happen, and that's something Doctor Who certainly isn't about - Chimes of Midnight least of all, when you consider its optimistic - though certainly not facile - coda.

However, this is the point I've been groping my way towards - black humour, as a sarcastic-hysteric mode of narrative, must have as its very impetus a spark of something indomitably, indestructibly human: the bare sense of indignation, of 'Bloody hell, can it really be right that things are this bad?'

And that's something Doctor Who has too. Both things ask the same question, perhaps a definitively Modernist one (cf. Mike Morris), but they ask it in wildly different ways.

Well, Shearman's lovely shiny Christmas gift to Who reunites these estranged cousins-many-times-removed with ease. His approach telescopes the schizo empathy/distance dynamic of black humour until it meets the Romantic-Humanist concerns of Doctor Who; the tension becoming that between caring and not caring, between enjoying a silly fun little story and understanding acutely that stories exist to address human pain. Mrs Baddeley harping on her plum pudding might be funny, but it's also terribly sad that this is the only way she can vindicate her existence. Likewise Shaughnessey's remark that Frederick's death wasn't that tragic because he was only the chauffeur and wasn't really needed. It is funny, and yet it's probably not that far from the real attitude to domestic staff of that time, the kind of people who've crushed Edith's soul. In those terms it isn't funny at all. And yet when you listen to the line... it is! Like I say, it's a constant tension. You cannot feel comfortable in the kind of story Robert Shearman writes, and IMO that's a very good thing.

An understated irony here is in the Doctor and Charlie being 'written into' a traditional Agatha Christie-type murder mystery. Murder mysteries have an oddly schizophrenic appeal too - they've become cosy fun things to enjoy in front of the telly with a nice hot cup of tea, even though murder is an obscenity and death itself is immeasurably terrifying. Shearman stated a similiar point more boldy in Jubilee, with the Doctor's comments on the irony of The Tower of London, a place of torture and despair, becoming a jolly tourist attraction.

'Oh fuck off Rob, the story's not really just about Edith!' you may say, 'It's also a cool ghost story about a house coming alive!'. And you'd probably have a point - on the terms I've stated, the emerging sentience of Edward Grove could almost be seen as merely whimsical, something fantastical to drive the story. But really the reason I'm less inclined to go on about Edward Grove than Edith Thompson is that I think the haunted-house-with-a-twist is something that's traditional within the 'language' of Doctor Who storytelling. It's the sort of thing we expect from a Doctor Who story. That's not to devalue it at all, because I think the 'mystery and wonder' language of Doctor Who is a hugely important part of its appeal (indeed to some fans, like Paul Magrs, it's perhaps the most important part). And I do also think Edward is also an apt combo of MacGuffin and subplot, reinforcing the themes of downtrodden victimhood and oppressive social order. Again, Shearman manages to pull forcefully in two different directions at once - poor old Edward represents faceless social order in the way he controls his denizens, Edith and co. being literally servants of the house and trapped in rituals whose only purpose are to keep the order and so the rituals going. And yet Edward also faces a horrible scenario of death-in-life closely which closely 'rhymes' Edith's. And unlike poor Edith, Edward does have to die - hence a subplot (that's such a denigratory-sounding term) which satisfyingly reinforces the 'main' plot by inverting it.

But for me Chimes of Midnight is best enjoyed as the story of Edith Thompson, refracted through a Cluedo board. It is, too, as purely enjoyable as Doctor Who gets, but it's Edith's focusing presence - like that of Eugene Tacitus in Holy Terror and Rochester in Jubilee - which really marks out what's original and unique in Shearman's approach to Doctor Who. Like its stablemates, Chimes is a contrasting collision of brutality and empathy, cruelty and caring. The caring always wins out, but the obstacles on the way make the victory that much more satisfying.

Now come into the living room and help me kill the Doctor.

Christmas Wouldn't Be Christmas by Jacob Licklider 22/11/18

The idea of the effects of a paradox was never really explored through the entirety of Classic Doctor Who. We did get stories about the effects of changing history in The Aztecs and The Time Meddler, but never showing just how fragile the Web of Time actually is. Father's Day from the New Series goes far into what can happen if fixed points are messed with, but The Chimes of Midnight did the idea first.

The story involves the Doctor and Charley landing in an Edwardian House on the night before Christmas where all through the house, not a creature was stirring. It is too quiet, as time seems to be frozen still, almost as if the Doctor and Charley have jumped a time track a la The Space Museum. When everything gets going, they find the dead body of the house's scullery maid and they get themselves confused for two detectives from Scotland Yard. This was as the clock struck 10:00. The house's cook is killed next as the clock strikes 11:00 and the Doctor and Charley realize just how deep the rabbit hole goes, as the two hours start repeating themselves in different ways and with different victims until we hit the twist. This is a plot that I just adore for just being so creative. The story acts as a Christmas Special, but it also acts as a horror story, with people being killed in gruesomely comedic ways. The twist of the story is also brilliantly set up and executed, which has grave implications for the Doctor and Charley. This is your last chance to look away before I go straight into spoiling the twist, so if you haven't yet go and get this story and give it a listen before continuing.

The twist of this story involves the scullery maid Edith Thompson who worked for the Pollard family as cook, where the young Charley was the only person who was nice to her. The announcement came to the Pollard estate that Charley had been killed on the R101 airship which in turn led to Edith becoming depressed and slitting her wrists. Charley, even though she was supposed to be killed on the R101 according to the Web of Time, was saved by the Doctor and, in an attempt to fix itself, the Web of Time took control of Edith's spirit and created the house which started to gain a mind of its own. This is all because the Doctor wanted to save someone's life. The story becomes a character drama with the Doctor having to find a way out of the paradox before they become trapped there forever.

Louise Rolfe's performance as Edith Thompson steals the show, as when she's alive she is happy but by Part Four, while she is explaining to Charley what happened to her, she has broken down into depression and is almost insane in that she wants to be allowed to rest or be allowed to live. India Fisher's Charley Pollard also goes through hell, as Edith and the house want to make her go crazy and kill herself in order to resolve everything. She is forced under hypnosis of the house for portions of the story, even becoming a child. She doesn't like plum pudding and once chipped her tooth on a three-penny bit, which the inhabitants of the house know of and try to get her back to a childlike state. Paul McGann as the Doctor is at his best here, as he has to be the one to figure out the mystery of the story. He knows something isn't right from the start, and he knows that everyone in the house is too one-note to be normal. The villain of the piece is the house, Edward Grove, which is a booming voice that represents a god of these two hours which are on a complete loop forever. The voice just sends chills down your spine.

The supporting cast of the story are all pretty standard as they are supposed to be one-note characters. There is Frederick the chauffer played by Robert Curbishley, who reveals part of the mystery, as he doesn't know what type of car he drives -- a Chrysler, which hasn't been invented yet, or a Bentley. He has an affair with the Lady's Maid Mary, played by Juliet Warner, which reflects Edith's affair. The head of the servants are Mrs. Badderly the cook and Mr. Shaughnassy the butler, played by Sue Wallace and Lennox Greaves respectively. They are both the prime example of stiff-upper-lip British servants, who only act on their master's orders from upstairs. Mrs. Badderly is famous for her plum puddings and is extremely pleasant, which are yet more clues as to how everything fits, yet she is just downright rude to those beneath her. The same can be said for Shaughnassy who is a kiss-up to his masters, as he wants to have his own personal gain, but he is almost verbally abusive to Edith.

The direction and music of this story have to get special notice. Barnaby Edwards directs this story as a very tight-knit space, as it does take place mainly in the servant's area of a home. It takes a particular skill for something like this to actually work, and Edwards is great at not only doing it, but doing it well. The music was done by Russell Stone, which is full of actual chimes as the clock plays a very important role in the story. Everything sounds like some sort of chime in a Christmas-music style but with an underlying atmosphere of something darker.

To summarize, The Chimes of Midnight is in one word perfect. Serving as a continuation to Charley's story arc, which you don't really need to have listened to the other parts to understand, and I just love every minute of the story. The acting is great, as everything feels undeniably British, from the supporting cast to the main cast, who act as the emotional centerpiece for the story. The direction and music of this story both complement the script and show just how dark the story is. There really is no excuse for you to not have heard this story, and it is deserving of its Limited Edition repress. 100/100