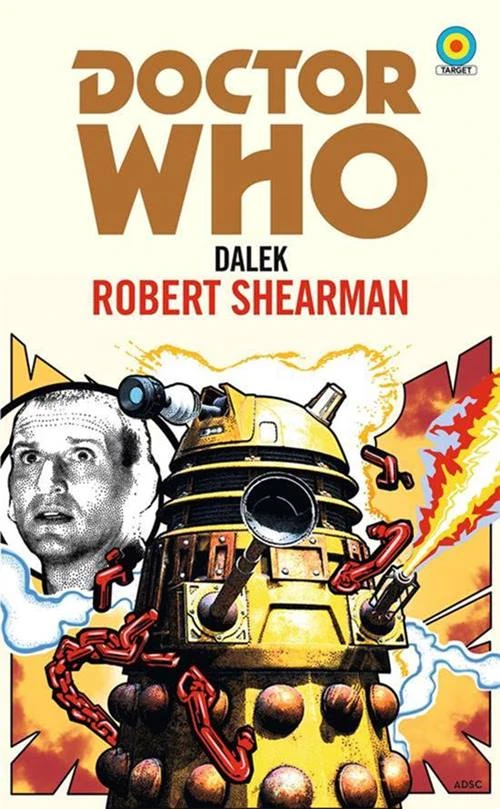

Dalek

Doctor Who - Dalek

|

Dalek |

Target novelisation Doctor Who - Dalek |

|

| Author | Robert Shearman |  |

| Published | 2021 | |

| ISBN | 978 1 785 94503 8 | |

| First Edition Cover | Anthony Dry |

| Back cover blurb: 'The entire Dalek race, wiped out in one second. I watched it happen. I made it happen!' The Doctor and Rose arrive in an underground vault in Utah in the near future. The vault is filled with alien artefacts. Its billionaire owner, Henry van Statten, even has possession of a living alien creature, a mechanical monster in chains that he has named a Metaltron. Seeking to help the Metaltron, the Doctor is appalled to find it is in fact a Dalek – one that has survived the horrors of the Time War just as he has. And as the Dalek breaks loose, the Doctor is brought back to the brutality and desperation of his darkest hours spent fighting the creatures of Skaro… this time with the Earth as their battlefield. |

Sympathy for the Devil by Niall Jones 31/5/23

To think about the Time War in the context of Doctor Who's transmission's history is to see it as a metaphor for the trauma of cancellation. It is a period of time that is not empty, just unrepresentable, reflecting the competing and often contradictory attempts to keep the series alive during the 1990s and early 2000s. For a viewer tuning into Series One of Doctor Who, however, the Time War is all about the Doctor.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Robert Shearman's Dalek, which presents the Doctor as a traumatised former warrior who feels nothing but hate for the enemy he fought. The Doctor may arrive in Utah with nothing but concern for a trapped alien sending out a distress signal, but when he finds that the alien is a Dalek, he becomes a man who screams at it 'Why don't you just die?' Christopher Eccleston's performance in the episode is nothing short of extraordinary. In the interviews on the final disc of Big Finish's Ravagers boxset, he discusses how filming came at a difficult time for him personally and that he channelled all his rage at his father's illness into his performance. What makes Dalek such an electrifying piece of television is that it not only makes the Daleks scary, it also makes the Doctor scary.

Given the significance of Eccleston's performance to the episode's success, how does the story work as a novelisation? The short answer is very well.

In novelising Dalek, Shearman closely follows the episode's plot beats and incorporates most of its dialogue; in addition, he adds two major innovations, which provide new angles on the story.

The first of these is the insertion of short chapters about the story's supporting characters into the main narrative. These chapters, which are described as 'tales', detail the backstories of Simmons, Henry Van Statten, Diana Goddard and Adam Mitchell, and recount just how they came to be working in a secret bunker buried deep beneath the Utah desert. Part of what makes these chapters so engaging is that they are stories in their own right, each with their own narrative drive and filled with unexpected twists and turns. They are also often quite humorous. For example, in 'The Collectors Tale', focused on Van Statten, the cosmologist Dr Yevgeny Kandinsky casts doubt on the extraterrestrial origin of the Dalek by noting that 'it is like a big pepperpot, yes?', while in Goddard's 'The Agent's Tale', Van Statten plays golf in Florida with an emotionally needy president who is unnamed but oddly familiar.

These biographies shift the centre of gravity away from the Doctor and towards the Dalek. While the Doctor does not appear in any of these chapters, the Dalek is present in all of them.

The centrality of the Dalek to the narrative is further emphasised by the second of Shearman's innovations.

The first thing that comes to mind when reading 'The Soldier's Tale' is that it recalls the novelisation's prologue, about a boy on a hill. In the prologue, it is clear that the boy stands for something else, but it is not clear what; by the opening page of the tale, however, the metaphor starts to become clear.

In the book, Daleks are not born evil. Instead, they are so thoroughly indoctrinated into an ideology of hate that they lose all capacity for joy and are stripped of their sense of self. Shearman's descriptions of this process are imaginative and highly vivid. He writes how 'a full seven seconds after he had been born, the child was taken from the nursery, and plugged into the emotional centres of the memory grid'. Here he was presented with the final, happy dreams of Dalek victims and tortured with them:

Remember that joy, the children were told.Here, Shearman draws parallels with totalitarianism and, in particular, with the Nazi ideology that inspired the Daleks, with its suspicion of individuality and doctrine of racial superiority. There is also a religious quality to the language used. The view that happiness was 'a delusion too soon snatched away' is described as a 'Grand Revelation', while the newly encased mutant is 'absolved of sin' now that it is no longer identifiable as an individual. The Parting of the Ways may have first presented the idea of religious Daleks, but it is more thoroughly explored here.Remember, and resent it. Remember what other life forms take for granted. That which will be denied you forever. Remember what they have and you do not, these creatures that are no better than you, no more worthy of happiness than you.

For you shall never feel peace. Or a cooling breeze, or the sunlight on your skin.

In considering the ideology that drives the Daleks, presented here as derived as much from self-hate as from a belief in their own superiority, Shearman offers a glimmer of hope. By suggesting that evil is never an innate quality --- whether in the sadistic Simmons or in a rampaging Dalek --- he implies the possibility that it can be undone. In unintentionally liberating the Dalek, Rose starts to change it. It becomes less of a killer, but choice for a Dalek is another form of torture. In its final moments, it is not rehabilitated; instead, in choosing to die, it clings to its fascistic ideology: better to commit suicide than to live on as something impure.

By centring characters other than the Doctor and Rose, Shearman provides new perspectives on the story. While the original episode will always remain a classic, the novelisation is arguably bolder. The presentation of a Dalek as an object of pity is key to the episode, but the novelisation goes further in its final chapters, asking what it might be like to be a Dalek. In short, Doctor Who - Dalek retains everything that makes the original great and adds what only literature can do.