Four to Doomsday

Doctor Who - Four to Doomsday

|

Four to Doomsday |

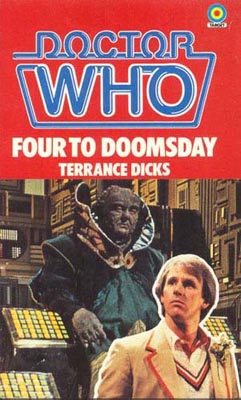

Target novelisation Doctor Who - Four to Doomsday |

|

| Author | Terrance Dicks |  |

| Published | 1983 | |

| ISBN | 0 426 19334 2 | |

| First Edition Cover | Photographic |

| Back cover blurb: When the TARDIS happens to materialise on an alien space craft the commander of the ship, the reptilian Monarch, invites the Doctor and his companions to continue their journey to Earth in his company. Monarch's hospitality even extends to a generous offer to liberate the time-travellers from the shortcomings of their bodies and replicate them as androids - so much more practical. Although Adric finds this proposal extremely attractive, the Doctor has good reason to be suspicious of Monarch's motives... |

"The exchange of two fantasies" by Jason A. Miller 14/4/13

No-one has ever loved Four To Doomsday. On the Ratings Guide's episode review page, Joe Ford, who finds something to love in almost any story not directed by Richard Martin, calls it a "nightmare"; Hugh Sturgess believes that one has to be "deluded" to believe that it's great or even good. Even I, an unabashed lover of the Davison era, usually find that the episode lulls me to sleep. I tried to write a review of the episode proper for this site back in, oh, 2001 or so, and never made it past one paragraph, which I've long since lost. In some ways, I appreciated Terence Dudley's script as visionary - he writes the plot of "V" before "V" became an American phenomenon in the early '80s - but it other ways, it's a bit of a soporific mess, which makes the story as televised a bit difficult to sit through.

For those reasons, this book should have been dreadful. Published in July 1983, it was Terrance Dicks' first 5th Doctor novelization, although he'd already written for the character on TV in The Five Doctors by that point. Dicks had spent much of his Target career writing adaptations of 3rd Doctor stories that he'd previously script edited, almost always managing to improve on the television episodes; and he'd written almost all of the 4th Doctor books, which is fortunate for us because his punchy, economical writing style was the perfect vehicle with which to convey Tom Baker's larger-than-life performance. But Peter Davison's 5th Doctor was a much more subtle creature than either Pertwee or Baker, and in Four to Doomsday he was trying on the role for the very first time. Watching Four to Doomsday on TV, there's not a whole lot of Davison to the performance, as most of the lines appeared intended for William Hartnell; he calls Nyssa "dear boy" at one point, and one is surprised when he doesn't refer to Adric as "Chesterfield", "Chesterman", or "Chartow" every five minutes. So, we have Dicks writing a novelization for a non-Pertwee or Baker Doctor for only the second time in six years (with only An Unearthly Child in the mix between mid-1977 and mid-1983), and it's a Doctor who hasn't quite figured out who he is yet, either. A recipe, perhaps, for disaster?

And yet, the book sails in print.

We'd find in Dicks' subsequent Davison-era novelization (Arc of Infinity) that he was not afraid to mock a script that he simply didn't understand. And, to be fair, there are moments in the Four to Doomsday novelization when one can sense Dicks rolling his eyes at the story. The "recreationals", lengthy dance sequences inserted presumably to pad out an under-running script, are called "interminable", and the Doctor notes "with some relief" when one particular dance finally ends. Terrance, who used to get to script-edit Robert Holmes and Robert Sloman, probably wondered just what Doctor Who needed with one dance sequence, let alone seven. He also demonstrates an unfamiliarity with the three companions, who admittedly come off pretty dreadful on TV: he doesn't appear to have gotten the memo that Traken was destroyed, even though he novelized that story the year before; he openly mocks Adric for his "bossy nature"; and he tells us that not only that "the best way to get Tegan to do something was to suggest the opposite", but further, that "Tegan could be exceptionally forceful, even for an Australian" (zing!). He also forgets to attribute Principia Mathematica to Alfred North Whitehead. When he describes the Urbankans as "super-intelligent technologically advanced frogs", one can imagine Dicks desperately wishing that Malcolm Hulke had still been alive to rewrite the script before it was handed off to the director. Lastly, he doesn't even try to rationalize an explanation, as he often did for other technobabble lines, Monarch's relieved declaration that "these will eliminate the need for telemicrographics."

But those are all early moments in the story, Part One on TV and the first three chapters into the book. As Dicks gets further along, things gather speed. He mocks the Doctor's awful joke about Lin Futu's name, helping to re-establish the character that Terence Dudley didn't quite know what to do with. What on TV appears to be the Doctor aimlessly wandering around, as Mr. Ford and Mr. Sturgess openly derided, Dicks grounds in reality: "The Doctor, as usual, was poking his nose into things, and hoping that some solution would present itself. It usually did, in the end." Monarch as a villain gets about a dozen terrific lines, making him one of the series' best humanoid enemies, right up there in terms of dialogue zingers along with other greats like Linx and Scaroth. Dicks wisely gets out of the way of long passages of sparkling expository dialogue, mostly in Chapter 7 (the Part Three material); on TV, this can all be a bit wearing, but Dicks sets aside his pointed asides for this chapter, and lets the conversations between Bigon and the Doctor, and between Monarch and Adric/Nyssa, shine in print. When Dicks doesn't like elements of a story, he mocks them in the novelization; when he enjoys them, he gets his prose out of the way, and the best parts of the story shine without his needing to puff them up. If he was in despair writing the first three chapters of this book, he was clearly having a ball during the rest of it. Best of all, he understands Monarch's villainy, and gets to deliver philosophical digs such as "a mistake that is not acknowledged cannot be corrected", and "the one thing about flattering tyrants [...] was that it was almost impossible to overdo it."

Be warned that this book is a bit of a relic of its time. Printed in 1983, based on a script written in 1981, Dicks has to include Dudley's belated critique of punk culture ("safety pins?"), and uses, without any hint of irony, the words "Chinamen" and "orientals" to refer to Lin Futu's crew. But all this can be forgiven, with 30 years' hindsight. Dicks distances himself from the bad characterizations: there's an incredible passage in Chapter 12 where Tegan throws a temper tantrum over her failure to pilot the TARDIS, which he elevates into "hysterical rage" and concludeswith "a kind of despairing coma", thus lending Tegan a gravitas in this scene which eluded Janet Fielding on TV. But, even better, Tegan observes shortly afterwards that "When the Doctor took charge [...], he really took charge."

Terence Dudley may never have written for the show before, and, playing the role for the very first time, Peter Davison really wasn't fully engaged with his character yet, but thanks to Terrance Dicks, the resolution to Monarch's plot is unmistakably the Doctor's show, and it's a good one.