THE DOCTOR WHO RATINGS GUIDE: BY FANS, FOR FANS

| Story No. |

226 and 227 |

|

| Production Code |

Series 5, Episodes 8 and 9

|

| Dates |

May 22 and 29

2010

|

With Matt Smith,

Karen Gillan, Arthur Darvill

Written by

Chris Chibnall

Directed by

Ashley Way

Executive Producers: Steven Moffat, Piers Wenger, Beth Willis.

|

|

Synopsis: The Doctor, Amy and Rory arrive in a tiny mining

village and find themselves plunged into a battle against a deadly danger

from a bygone age.

|

Reviews

A Review By Harry O'Driscoll

7/7/10

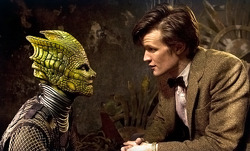

When I heard that this story would feature the return of the

Silurians, I knew this would be tough to get right.

After Warriors of the Deep, I thought that the Silurians would be again depicted as a one-dimensional group

of baddies, who were totally evil and it was the Doctor's mission to

destroy them. Thankfully after watching it I blew a sigh of relief that

they had pulled it of excellently.

The first episode is a bit of a waste admittedly, with everybody doing

nothing and the whole thing didn't look like it blew the budget exactly.

However, the second episode changes that with some great shots of the

Silurian city which has all the atmosphere of a different

world. The whole re-design of the Silurians wasn't great with them

looking too human for my liking. Why did they get rid of the Third

eye? However, the added advantage is that the Silurians are

more individual and much more relatable and credible as characters. The

story succeeds wonderfully in showing the two sides of the Silurians,

with Eldane coming across as my favourite of the whole story. Of all the

characters, he comes across as the most reasonable and the most eager for

peace. The conference with him, Amy and Chaudhry is one of the episode's

highlights.

The humans in this story are portrayed in an interesting light while

actually not coming across definitely as the good guys. If you ask me

the biggest villain in this story is Ambrose. Although the

Silurians had kidnapped several people and Alaya was hardly

pleasant, nobody had been killed and she was the first one to actually

kill anybody. And then when Ambrose proclaimed to the

Silurians "This is our planet", I can hardly blame Restac for wanting to

kill her. It works to prove a point that humans are hardly all peaceful

and that it was people like Ambrose and Restac who ruined the chance for

peace. It's a very good morality story.

At this late stage in the season, we begin to get closer and closer to

that finale. In order to avoid spoilers I won't divulge what happens but

it makes a very poignant moment that feels like it'll be revisite. The

final scene is a very chilling and intriguing moment that leaves you eager

to find out what happens in the finale.

Rio doesn't have a big mining thing! by Evan Weston

9/10/17

I have to be honest here. This is the first Moffat-era episode that genuinely disappointed me upon rewatch. Not that it's bad, not at all - we're just in the middle of a mostly strong run, and I remembered The Hungry Earth/Cold Blood solidly continuing the trend. This is a good story, but significant flaws and, continuing a very different trend for Doctor Who, a senseless and non-applicable political statement holds this one from greatness.

It's got a lot going for it. The elephant in the room going in was the redesign of the Silurians, and that has been pulled off marvelously by the production team. The Silurians look better than almost any old Who enemy done previously (with the possible exception of the RTD Daleks), appearing perfectly natural in both their stunningly realized environment and against their human counterparts. Overall, this is one of Doctor Who's best-looking episodes, with the industrial, dull near-future Welsh countryside balanced perfectly by the wondrous Silurian underworld. The drill's presence is felt through the entire first half, and yet we never lay eyes on it. This is tremendous work once again by Moffat's behind the scenes crew, who deserve to be commended at every opportunity.

For the most part, Chibnall's script keeps up with the set design. He waits about 35 minutes before Matt Smith declares "I know who you are," and the first time I watched this, I had no clue the Silurians were returning. The build-up of The Hungry Earth is very nicely done, with Amy getting sucked down fairly early and the stakes ramping up considerably throughout. We're also introduced to the strong ensemble at a good pace, and the script allows us to become invested in each of them individually before we see them put through their paces. Quickly, though, Cold Blood loses this momentum somewhat. We know what the reaction will be when the dead Alaya is brought down, so the whole "negotiation" scene feels rather pointless. This leads the episode into wasting 20 minutes of the viewer's time, which is perhaps its biggest sin. The climax regains a good deal of the strength though, and the ending (which we'll broach in a minute) is genuinely shocking.

What is mostly a good story though is bogged down not just by its fruitless second-half padding but also by a few significant plot holes that I can't overlook. The Silurian backstory - and mind you, this isn't necessarily The Hungry Earth/Cold Blood's fault - is completely convoluted. I can accept that a race lived on Earth before humanity; that's fine. But a species this advanced surely wouldn't believe so deeply in a prophecy as to send itself underground for millennia, right? It seems boldly out of character, and nothing makes much sense down there, either. Why was Malohkeh, characterized as a pretty good dude, experimenting on humans? And why is the military obsessed with rank at one moment and totally insane the next? In addition, we have the instigating device of Elliot's capture, which is also very contrived. The Doctor just lets him wander off into the field with three minutes to go? And where's his mother?

Speaking of lovely Ambrose, she's almost written as too nasty. I included her on the list of villains for the episode, and she's very nearly the main antagonist. Nia Roberts plays her as despicable, or perhaps she's attempting to make her motivated by saving her child and failing. Regardless, she never really redeems herself, and seems more pressured by some blind jingoist ideology than love for her son. This gets into the political statement the episode is trying to make, "people probably shouldn't needlessly fight each other," which is almost as stupid as Planet of the Ood's "slavery is bad." Okay, it's not nearly that silly, but Ambrose and her Silurian counterpart - Restac, who happens to be a far more successful villain in her own way - are way too one dimensional for the message to mean anything.

Still, I can't deny Restac's appeal, and it's no small wonder that Neve McIntosh returned as Vastra the next season. She looks great in the makeup, and her Silurian (unlike Dan Starkey's Sontaran in The Sontaran Strategem/The Poison Sky) achieves the desired effect. Good on Moffat for inviting her back. The supporting performances of Robert Pugh and Neera Syal are genuinely moving, and they're two of the better guest spots in Series 5. Syal, in particular, brings a warmth and curiosity to Nasreen, and the romance between the two feels genuine. Samuel Davies is adorable as Elliot, and Stephen Moore brings the appropriate gravitas to the Silurian leader Eldane.

Our principals also turn in a generally strong effort. Karen Gillan doesn't do much except get sucked down in the first half, but she's solid in Cold Blood, and her attempts to remember Rory are heartbreaking. Matt Smith plays off her very nicely as usual, and his more serious moments here are used to great effect. He does embrace the Doctor's role as worldbuilder in the second half though, and that doesn't feel right with the character. Arthur Darvill turns in perhaps his least memorable performance so far, but he's still just fine. Rory's sacrifice near the end of the episode is tragic, and he does very nicely in making us feel his pain. The ending itself is a bit problematic, though - Amy remembers the clerics from The Time of Angels/Flesh and Stone because she's a time-traveler, but she forgets Rory nearly instantly. This is explained by a one-liner about Amy's personal connection to Rory, but it feels tacked on and it's clearly done just to set up the next stage of plotting. It's the first real piece of bad arcplot in the Moffat era, and it sets up a trend that gets significantly worse in Series 6.

I suppose we can't hold that against The Hungry Earth/Cold Blood though, which brings the troublesome Silurians back as best it can, with straight-up terrific production values and one of the more solid supporting casts in the show's history. It's still the fourth straight "good" story in a row after the series' shaky start, and it's worth a watch just to see the old monsters and have a good bit of fun. Series 5 takes a weird and interesting turn into the Moffat-ier aspects of this era from here, but this one feels like good old Davies Who two-parter: rifled with problems, but entertaining nonetheless.

GRADE: B

"Playing with only one ball..." by Thomas Cookson

28/4/20

If there's one unfortunate takeaway from Chibnall's tactless onscreen 1986 slating of Pip and Jane and subsequent Torchwood work, it's this. He's afraid of the show losing its youth street-cred again and thinks the JNT/Saward era's problem was, if anything, that it wasn't mean-spirited enough.

This might be why, despite being pleasantly surprised by his impressive Broadchurch work, Doctor Who seemingly brings out Chibnall's worst. A fanboyish desperation to give the show newfound schoolyard coolness via cynically indulging trashy shock violence and sex. I think why this story feels so nasty, so histrionically at odds with Series 5's tone. Perhaps Chibnall anticipated writing for a more horror-centric Moffat era.

In terms of why Chibnall got the Silurians' story (when their story should've ended in 1970), perhaps Moffat knew that a reduced budget necessitated more Earthbound stories. Perhaps, just like Malcolm Hulke, he feared Earth-invasion scenarios were getting tired, and his monster-centric era might get old without some variety involving monsters who aren't really monsters, who have different, understandable motivations.

Whenever the show does this, the Silurians become subject to cultish sycophancy by the show's hero, for being apparently slightly against the cliched norm, and shame on us for not seeing it. Each time they become less an interesting monster race and more a bunch of spoilt, entitled, vindictive brats we're lectured to tolerate.

Fans seemingly think we should keep entertaining their 'legitimate grievance' that nature usurped them while they slept and they can't plague-bomb apes without facing massive retaliation anymore. Each revival is tailored toward the 'true believers', who deify Hulke's message beyond its original intent.

The conceit of 'fixing' Warriors with a bigger budget and taking Johnny Byrne's patronising suggestion that redesigning the Silurians to resemble more humanoid Nazis might've aroused more audience sympathies, is rather shallow. It's an incredibly unambitious story, making its one ambition - to pull a massive guilt-trip on audiences - feel particularly nasty.

The Silurian stories almost resemble the Saw franchise. A lucky one-off success that was never really intended to inspire its contrived follow-ups that had to place undue pious import on its titular monster(s). Going to distorted, cultish extremes to characterize the vindictive monster(s) as uniquely 'noble', 'well-intentioned' and the victims inspiring their Godly wrath as somehow uniquely unforgivable just for being human.

This certainly emulates Saw. Elliot's flash abduction, during Matt's inexcusable negligence, strongly echoes Jigsaw's carpark abductions whilst donning a moose-head. Likewise, Amy trapped within the glass, facing dissection.

I can understand some fans feeling Warriors' live-action Thunderbirds aesthetic had more charm (before it felt the insecure need to assert its desperately 'adult' mean-streak). Perhaps to Chibnall's mind, he's just updating Hinchcliffe's Hammer pastiche approach by emulating modern horror's nastier trends.

It goes beyond aesthetics though. It's the story's moronic attitude. How the Doctor demonstrates his moral superiority and begins peace negotiations by hunting one Silurian like an animal and taking them hostage.

Sure, at least (to damn with faint praise) it suggests the Doctor's spent the decades since his last failure imagining what he could've done right instead to compel peace, rather than new ways to virtue-signal his sadness that he apparently still can't find "another way". The problem is, it's among his stupidest ideas.

To understand the kind of modern horror Chibnall's emulating, let's explore how horror's changed over time. It's not that 1980's horror wasn't nasty and gory. Indeed, modern horror is so gory largely in nostalgic emulation of that 80's era. However, the emphasis has become more heartlessly mean.

The original 1984 Nightmare on Elm Street had its gruesome vignettes. But their budget limited how few gory deaths they could achieve. So each death had to actually matter and carry emotional impact. Galvanizing the heroine to finally, affirmingly fight back.

Saw's budget allowed them to do far more non-sequitur torturous kills, with the only purpose being showing someone fail their test. Suggesting these victims deserved it. Perhaps now that slashers aren't about punishing teenage permissiveness anymore, Saw had to rapidly, incoherently contrive new deadly sins for its victims.

There seemed a need to pretend these films were moral lessons for its victims (but not Jigsaw, as there's clearly 'enough' good in him to not need redeeming). They'd 'fallen', sinned or lost grasp of life's worth. And were required to behave like douchebags to prevent audiences questioning the overriding moral bankruptcy (namely that Jigsaw must've been stalking them long before finding any spurious dirt on them to retroactively justify his obsession).

Likewise, Ambrose's family are quickly taught to cultishly recite the Doctor's preachings like puppets, blaming each other for Ambrose stupidly killing Alaya. Even Elliot treats her contemptfully, to maintain the illusion of a moral point. Despite having been abducted, he's disgusted when the mother he dreaded he'd never see again killed his abductee. Because we're meant to be too. That's why Nightmare in Elm Street's terrorized characters feel like real people we could champion; Ambrose just feels here to intermittently be the writer's meat-puppet and the kind of despised pariah mother painted in distorted tabloids for the baying mobs.

Barry Letts reportedly trimmed The Silurians' ending for being too confrontational in condemning mankind as the 'lesser' species.

The problem with this and Warriors isn't just that they're confrontational. They're clearly 'true believer' fanboy works that seem confused as to what they're supposed to be confrontational about.

It might've been reasonable in Pertwee's era. Hulke wasn't just tutting his finger at our violent responses but showing the inherent, unstoppable horror of the military war machine, where arbitrary attack orders given from high must be robotically obeyed and can't be dissuaded.

This tries to apply that critique to natural family solidarity. Taking Ambrose's understandable mothering instinct to protect Elliot, it suggests something shamefully narrow-minded about her failure to trust his abductor's goodwill or her determined lengths to recover him. It's the ultimate fannish, cultish conclusion. If only we could get the kids young, they'd love the Silurians and hate their parents for reacting so 'intolerantly' to their child's abduction.

Even Matt's "I'm asking you nicely, leave it" feels nasty. It doesn't address why Ambrose felt she needed a weapon, nor does he reassure her he can rescue Elliot peacefully. Almost making it self-fulfilling that Ambrose will do the wrong thing by forbidding any precautions. Ambrose is at fault for failing this test of character. But only as the victim. Whoever abducted Elliot, and then taunted and terrorized her, they're beyond reproach. Worryingly, many fans wanted to see revenge on Ambrose (for essentially doing exactly what Amy later does to Madame Kovarian for the same reason).

We're not even supposed to doubt Matt's sureness to negotiate peace. So where's the tension? A reversal of Hulke's writing, where it seemed so easy to avert war, making the wrong choices more devastating. At least I can believe that Matt's Doctor, unlike Davison, wants humanity to be better than we are, rather than deader than we are, and actually wants to avert war rather than prolong it.

But, unnervingly, only the fact that Elliot's abductors are Silurians differentiates Ambrose from Jodie Whittaker's character in Broadchurch. It's all that makes Ambrose a hate-figure between the two. But we're not meant to care. We're only meant to despise Ambrose and consider her uncool for not recognizing the Doctor's awesomeness.

We were somewhat led to pity Broadchurch's child abductor, but only during his most vulnerable, pitiful position of having to confess, revealing he was trying to resist his paedophilic tendencies and avoid hurting anyone. It didn't demand we unconditionally forgive him without undermining his powerbase (after his silence caused more deaths). Whereas we're expected to hate Ambrose for not forgiving unconditionally.

Unfortunately, it almost makes the case for the torture methods it condemns, given Ambrose fears she'll never get Elliot back otherwise. There's something nasty about how it's humanity's best mothering instincts that earn condemnation. It's horrible. Revealing nothing about our human condition or misunderstandings. Just demonstrating how a spiteful, evil Silurian willing to die to ignite senseless war can terrorise and taunt a distressed mother into killing her with the most survivable millisecond's tasering. How insightful.

Sure Ambrose's actions weren't self-defence, but her hesitance suggests she hadn't entirely committed to go through with murder. It's difficult calling her actions a human-rights abuse, given Alaya's creepy determination to fall on someone's sword. But then Jigsaw was willing to die to condemn his victims too.

It jars this season, given Matt's Doctor was emphasised as having darker sides (Amy's Choice). His pious reprimanding of Ambrose feels disconcertingly at odds with him attacking Daleks unprovoked with a spanner or forgiving Vincent's killing of the misunderstood blind dinosaur.

You might say the Doctor's anti-human paranoia is proved right, and Matt plays the devastation believably when Ambrose carries Alaya's corpse back. But it was Alaya who determined to make this happen. Because Silurian stories don't work in any format shorter than Pertwee six-parters unless they involve crazy Silurian provocateurs determined to accelerate a crisis.

Pertwee's misanthropy made sense, as a stranger in a strange land, unsure who's side he's on. But less so for Davison or Smith, who'd befriended humans for decades. Despite claims the alien Doctor might plausibly grant greater respect to Silurians as Earth's original inhabitants, nothing onscreen since justifies why he should continue to. Any rare surviving Silurians he's met since have been progressively nastier pieces of work.

Adrian Sherlock suggested that, because Silurians aren't programmed creatures like Daleks or Cybermen, it justifies his continued hysterical insistence that they're potentially reasonable. Had someone suggested Rwanda's genocidal Hutu militias aren't sci-fi robots, and therefore can be reasoned with, it'd be unimaginably crass.

Such conflicted loyalties were once part of the Doctor's more challenging development. But they've since turned him into a defective broken clock. In 1970, the Silurians' civilization destabilizing into bloody coups and militias made the same sense as in East of Elephant Rock.

But why are Silurians now breeding Jihadist martyrs? The Silurians see humans like we'd see a home rodent infestation. Would we seriously martyr ourselves to eradicate that? Suicide bombing doesn't make sense without understanding the historical reasons Hezbollah spearheaded that precedent in Lebanon. You can't just depend on that allegory without it making sense.

It avoids Warriors' appalling ending by lazy cop-out. Restarting us on a blank slate, rather than tarnishing something already concluded with a nastier finality. Postponing the dilemma another millennium. The hibernation process conveniently pouring toxic gas around the stasis pods to kill our villainness, to make things even more breathtakingly pat. So what was the point, beyond toy sales?

Rory dying amidst another senseless Silurian-human war could've been genuinely poignant, but the histrionics and preceding suspiciously manipulative, insincere dialogue kill it quick.

Despite loving Series 5 thus far, this was mean-spirited enough to make me nearly stop watching. I felt suddenly I was being told Doctor Who wasn't so welcoming and I now had to agree with its vindictive scorn for human instincts, otherwise I'm not a true fan. Despite how, back in Robot, we relished Sarah's mocking the Scientific Reform Society's brainwashed cranks.

I don't know if Chibnall truly believes Davison had the right ideals and message if you contrived the right circumstances to vindicate him. Or echoing what he thinks he's supposed to believe as a Who fan writer. Chibnall seems like a writer trying badly to reconcile his trite liberal politics with a nostalgia for reactionary horror cinema.

Which defines Chibnall's problem. Everything he writes for the show feels emotionally forced, histrionic, insincere. When he attempts RTD's happy families and children's morality preachings instead of Torchwood's torture porn, it comes off as unnerving.