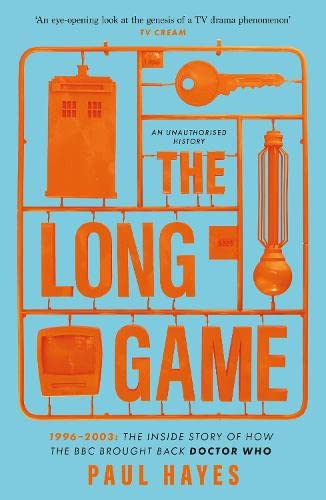

The Long Game

The Inside Story of How the BBC Brought Back Doctor Who

|

|

Ten Acre The Long Game The Inside Story of How the BBC Brought Back Doctor Who |

|

| Author | Paul Hayes |  |

| ISBN | 1 908 63080 3 | |

| Publisher | Ten Acre | |

| Published | 2021 |

| Summary: When Russell T Davies’ triumphant Doctor Who relaunch hit screens in 2005, it didn’t simply appear out of nowhere – the show’s journey back to television was long and complicated. The years since the last attempt to revive the programme had seen enormous changes at the BBC, not least in the Drama department; along with battles between different parts of the Corporation over who should get to bring the Doctor back to the screen; and even doubts over whether or not the BBC still held the rights to make the show at all. The Long Game is the story of those conflicts and setbacks, during a transformative time for the BBC. It’s a story told by those who were there, including BBC One Controllers Lorraine Heggessey and Alan Yentob, drama bosses Julie Gardner, Jane Tranter and Mal Young, BBC Worldwide executives Rupert Gavin and Mike Phillips, and BBC Films head David Thompson – many speaking in depth for the first time about the part they played in the attempts to bring back Doctor Who. |

The Space Between Worlds by Niall Jones 29/6/24

Paul Hayes admits that the period from May 1996 to September 2003 is, on the face of it, a strange part of Doctor Who's history to write about. After all, it's a period characterised by absence. Following the failure of the TV Movie to lead to a new series, the show seemed completely and utterly dead. Despite this, 2003 ended with Lorraine Heggessey, then Controller of BBC One, announcing that Doctor Who would be returning to TV, with Russell T Davies as its head writer.

How Doctor Who went from the ignominy of a failed US pilot to, once again, becoming the biggest thing on TV is the story which The Long Game tells. Like Hayes's 2023 book, Pull to Open, The Long Game closely examines the landscape of British television and re-creates the world into which Doctor Who re-emerged. Using a wide range of sources, as well as interviews with a number of key players, Hayes reveals that, despite its long absence from our screens, Doctor Who in the late 1990s and early 2000s was far from dead and buried. In fact, the story at the heart of The Long Game is not one of death but of resurrection. During this period, Doctor Who was like a submarine attempting to surface, just visible as a glint of dark metal beneath the water.

For fans, perhaps the most contentious, frustrating and even dispiriting attempt to bring Doctor Who back came in the various rumours of a Doctor Who film. These rumours emerged periodically, often in the tabloid press, and sometimes with big Hollywood names allegedly attached to the projects: Denzel Washington, Anthony Hopkins. Fans could be excused for feeling cynical about all this. After all, these rumours never came to anything and were often revealed to have been based on little more than hearsay and misinformation. Hayes emphasises, however, that at least some of these attempts were in fact serious. In 1999, reports emerged that writer and director Paul W. S. Anderson, known for his video game adaptations and for the cult sci-fi horror film Event Horizon, had written a treatment for a script at a time when BBC Films were looking for a hit. Although this didn't result in a finished product, it does show that, even at a time when Doctor Who appeared to have failed, it remained something that people in the film and TV industry wanted to make.

While the question of whether Doctor Who is suited to the big screen has always been contentious, the biggest controversy thrown up by the idea of a film concerned rights issues. Throughout this period, there was a persistent rumour that attempts by the BBC to make a Doctor Who film were preventing the Corporation from commissioning a new series. In fact, concern about this issue eventually became something of a headache for the BBC, owing to the sheer number of emails they received on the subject. Daniel Judd, a researcher for the fledgling Doctor Who website, recounts that 'every department in the BBC, if there was an external-facing e-mail address, had to answer every e-mail that came in'. As a result, every time Lorraine Heggessey and Controller of Drama Commissioning Jane Tranter 'went on record saying there were rights issues, we'd suddenly get thousands of e-mails and had to answer them'. The solution to this problem: an online FAQ statement. In the end, this statement revealed that the question of rights issues had been a red herring all along. Universal's rights to Doctor Who had reverted back to the BBC once it became clear that they weren't going to commission a series and, while the BBC was indeed interested in making a film, that did not prevent the Corporation from making a new series.

While it's understandable that much of the attention directed towards Doctor Who centred around whether or not it would be returning in live-action form, Hayes highlights the fact that, during this period, new Doctor Who was being made, albeit in other media. In 1996, anticipating huge merchandising success off the back of the TV Movie, the BBC announced that they would be taking the licence for original Doctor Who fiction away from Virgin the following year and publishing books in-house instead. While this initially looked like an expression of faith in Doctor Who, the TV Movie's relative failure meant that the brand became something of an oddity, with the BBC largely abandoning it to editor Steve Cole.

Two years later, in 1999, Big Finish began releasing Doctor Who audio dramas, with a number of Doctor Who actors reprising their original roles, suggesting that if the BBC weren't going to make Doctor Who, then someone else would. While having the likes of Sylvester McCoy and later Paul McGann starring as the Doctor made Big Finish's dramas the closest thing to a new series of the show so far, the lack of visuals emphasised the distance between this and what Doctor Who was on TV. Big Finish's success nevertheless showed that there was still an audience for Doctor Who, perhaps even for a new series.

This isn't quite what Death Comes to Time was, although it had been intended to launch a new series. Initially proposed for broadcast on BBC Radio 4, the serial ended up being released on the BBC's Cult website as a series of audio episodes accompanied by partially animated illustrations by artist Lee Sullivan. Death Comes to Time proved popular; when the pilot was released on 13 July 2001, it was accessed by 100,000 users, creating 1.6 million page impressions.

Although the success of Death Comes to Time -- and, later, the animation Scream of the Shalka -- highlighted the continual popularity of Doctor Who, the fact that they debuted online marked them out as being of marginal interest, popular among a small subset of online-savvy fans. These fans may have been the same people who were active on the various Doctor Who websites that emerged in the late 1990s and early 2000s, such as Gallifrey Base and, indeed, this one. The fact that Doctor Who was being launched online suggested that the episodes' makers did not expect it to return to TV or be popular with mainstream audiences. Even when it was on TV, as in the case of rare repeats, it was broadcast in a cult slot on BBC Two, largely reserved for American imports, such as The X-Files. Of course, the books and audio dramas played a role in keeping Doctor Who alive, but they were largely made for existing fans. With a couple of notable exceptions, such as the bestselling novelisations of the original Star Wars films, TV tie-ins are considered a niche market, associated -- rightly or wrongly -- either with children or with a particularly obsessive type of fan. They don't create water cooler moments or seep into a nation's collective consciousness.

It is possible to imagine a world in which Doctor Who eventually became a purely cult phenomenon, existing solely as books and audio dramas bought by hard-core fans, as it slowly faded from popular memory. However, this was not the case in the UK at the turn of the millennium. In fact, the BBC were repeatedly flooded with letters asking for Doctor Who to be recommissioned and the show performed well in audience polls. In 1996, it was even voted the BBC's 'Best Popular Drama'. In 2000, a poll of TV industry professionals conducted by the British Film Industry named it the third greatest British TV show of all time, 'behind the hard-hitting 1960s drama Cathy Come Home and the classic 1970s sitcom Fawlty Towers'. Even the BBC themselves, often accused of being anti-Doctor Who, clearly considered it one of their all-time classics. When, at the 1996 TV 60 awards, they put together a montage to celebrate their 1960s output, Doctor Who was represented in the form of a clip from The Power of the Daleks.

Considering all this, the question at the heart of The Long Game is transformed from 'Why did Doctor Who return?' into 'Why did it take so long?' After all, Russell T Davies held his first in-person meeting with the BBC about Doctor Who sometime between September 1998 and January 1999. Several of the other key players involved in the revival -- Lorraine Heggessey, Jane Tranter, Mal Young -- were also in their positions by the year 2000. (Julie Gardner joined three years later.) One of the biggest myths that Hayes busts in The Long Game is the idea that the BBC were hostile to Doctor Who. In fact, the book reveals that it was full of people who had grown up loving the show. Hayes includes an anecdote about Helen O'Rahilly, then a channel executive at BBC One, keeping a toy Dalek on her desk and pressing the 'exterminate' button whenever Heggessey, her boss, arrived for work. Eventually, this wound her up so much that she agreed to organise a meeting to clarify the rights issues just to make it stop. In Heggessey's recollections, it was a model TARDIS on O'Rahilly's desk that inspired her to bring back Doctor Who, but either way, the story illustrates that the show had supporters within the BBC.

Alongside its exploration of Doctor Who itself, The Long Game also looks at the ways in which British TV was changing during this period, from the decline of videotape to the return of Saturday evening as a ratings success. By including detailed context, Hayes highlights the way in which the re-emergence of Doctor Who was shaped by ongoing trends in British media. For example, the success of Casualty showed that, contrary to conventional wisdom at the time, there was space for Saturday evening drama on the BBC. As with Pull to Open, Hayes also writes about the wider careers of key players in Doctor Who's story, further highlighting its connections to other parts of the broadcasting landscape.

The Long Game illustrates not only that there was no conspiracy against Doctor Who, but that the second half of the Wilderness Years consisted of almost continual attempts to bring it back. That it took as long as it did to return was down more to bureaucracy, confusion and miscommunication than anything else.

For a long time, it seemed a cruel irony that the final serial broadcast before Doctor Who's 1989 cancellation was called Survival, but, in the end, it turned out to be a prophecy.