The Power of Kroll

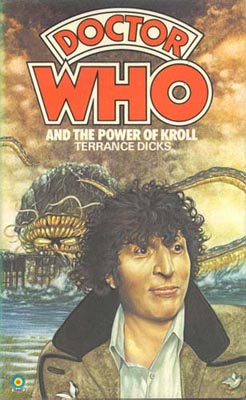

Doctor Who and the Power of Kroll

|

The Power of Kroll |

Target novelisation Doctor Who and the Power of Kroll |

|

| Author | Terrance Dicks |  |

| Published | 1980 | |

| ISBN | 0 426 20101 9 | |

| First Edition Cover | Andrew Skilleter |

| Back cover blurb: The huge, octopus-like Kroll lived deep in the swamps of the humid, steamy planet. To the native swamp-warriors, Kroll was an angry, mythical god. To the money-grabbing alien technicians, Kroll was a threat to a profit-making scheme. In their search for another segment of the Key to Time, the Doctor and Romana have to face the suspicion of the Lagoon dwellers, the stupidity of the technicians and, finally, the power of Kroll... |

A little less Bakered by Tim Roll-Pickering 7/2/06

As he looked at the gaping muzzle of the blaster and at the mad eyes above it, the Doctor realised that at last he'd made one joke too many.There are numerous stories about how Tom Baker stamped his mark on the series so completely in the late 1970s, often exagerrating heavily the character of the Doctor beyond what was written in the scripts and being a complete nightmare for directors. Some have even wondered what the series would have been like if the directors had had less control, perhaps under the 1960s conditions of almost continuous recording of an episode in one go. Others have been grateful that advances in editing have saved people from this. But one has to wonder just how far and at what point the scripts created the Doctor of this period.

Most of the novelisations from this time are heavily based on the camera scripts, sometimes to the point of being little more than prose renditions, so it is interesting to note the amount of humour present in the book version of Doctor Who and the Power of Kroll. Here the humour is still present, such as the Doctor babbling about windows and Dame Nelly Melba whilst being stretched on a rack, or reminding a gun-toting Thawn that he's neglected to say "Don't make any sudden moves" (which Thawn automatically repeats) but overall the impression given is of a more subdued and focused Doctor than onscreen. The Power of Kroll is the script that Robert Holmes was least happy with (even down to rehashing elements such as the gun running, the setting up of one side against the other by an ambitious man or the lone rampaging monster in The Caves of Androzani) and even in book form it's hard to escape from the story's trappings as a tale of fanatics not realising the reality of the situation around them in a setting that parodies colonialism. Dicks tries hard, particularly by giving little additions such as the Swampies' desperation that leads them to follow Ranquin's fanaticism when all their other certainties are smashed aside, but in other places the characters remain a cipher, particularly Ranquin himself whose devotion to his faith in Kroll, even to the point where he does not run just before he is eaten, is not explored as well as it might be.

An isolated outpost on a moon does not lend itself to a grand cast or setting, but Dicks does at least succeed in keeping the story moving. However it is hard to avoid some of the story's failings, particularly the ending which comes as close to "waving a magic wand" as almost anything seen in the entire series. But compared to some of the other novelisations from this period this book does not leave the reader feeling totally empty at the end and it does manage to pack in some good moments, such as Kroll's thoughts as it attacks the refinery. 5/10

Holmes is Where the Art Is by Jason A. Miller 30/7/19

It's easy to overlook the novelization of The Power of Kroll. I sure did: it holds the sad distinction of being the very last of the original run of Target paperback novelizations that I ever bought (at a Doctor Who convention in Chicago in November 1996, on the same day that I first met Robert Smith? -- a momentous night for two different reasons, then).

However, this book is deceptively terrific. You have to overlook a few things to enjoy it, of course. First, the TV story. Not Robert Holmes' best script, but, you can hardly blame him, as he put all his chops into The Ribos Operation, which came out just a few months earlier. The TV production benefits in part from striking location visuals, but suffers from limp acting and that Kroll prop. Oh, my. Even in the context of 1978, it beggared belief.

The book dispenses, of course, with the TV visuals, which means that you lose the marshes and hovercraft and convincing green aliens on the one hand, and the woeful acting and Kroll prop on the other. All that's left are Holmes' words... and, to quote an observation by Chris Bidmead, preserved on the text commentary to the Castrovalva DVD release, words were Doctor Who's best special effect. And here you have Holmes' script and concepts laid bare -- and who was a better world-builder than Holmes? -- and filtered through the crystal clear prose of Terrance Dicks, who never wastes a word and who never lets a sarcastic observation slip by.

While the script may not be Holmes' best, Dicks writes as if it is. Dicks includes an epic prologue introducing us to the Kroll creature. He gets off an impressive line on his opening page, about the moon of Delta Magna: "It was no place for men -- but men lived there all the same. The shuttle craft touched down on the Refinery's tiny launching pad, discharged its solitary passenger and his bulging travel-bag, and took off as if it couldn't wait to get away again." It's hard to argue with this kind of prose; I love his characterization of the shuttle craft, for example.

The cast of characters in The Power of Kroll is largely made up of the most cardboard of stock characters, for whom the phrase "one-dimensional" would be high praise. Nobody in this story really changes (and there are only two or three proper cast members who survive, anyway). Put it this way, Holmes named one of the Refinery characters after that character's eventual death scream ("Haaarrgh!"), and named one of the Swampies "Skart", which sounds awfully rude, for two or three different reasons.

Dicks wisely introduces all the Refinery characters in a single paragraph but makes his words count and ties it all together with a Shakespeare quote, giving these characters a richness that they most certainly did not deserve:

"Fenner, dark, round-faced with a look of irritable gloom, as though he had some perpetual grudge against life. Dugeen, young and eager yet with an air of nervous tension. Harg, amiable enough, but often quiet and withdrawn. Thawn himself tended to be silent and uncommunicative, so they weren't exactly a happy band of brothers".Dicks also dives straight into the political subtext of the presence of this Refinery on a planet that's basically an Indian Reservation -- and, as the Doctor Who production office's resident Tory, Dicks delivers a surprisingly fine piece of left-wing agitprop, commenting on the situation:

"Delta Magna was their home world, a bustling, heavily industrialised planet. Reasonably Earth-like, it had been one of the first to be colonised. Now, like Earth itself, it was over-developed to the point where its teeming population was running out of both space and food. Hence this refinery."

Dicks even straight-up makes note of the reservation comparison, mentioning the "Red Indians of Earth" -- you could say the phrase "Red Indian" in a children's book in 1980, I suppose, but let's hope Terrance is not still running around saying that, 39 years later.

When the Refinery's lone Swampie servant (amusingly named Mensch, a word that has strongly benevolent connotations for those of us Americans descended from Yiddish-speaking ancestors) enters the room, "None of the four men in the room spared him a glance". A few passages later, as Harg calls the Swampies savages, "No one so much as glanced at the Swampie servant in the doorway." Dicks lets you know right away that these humans aren't heroes or role models and that the Swampies have good reason to shortly start fighting back. The Swampies are not portrayed as simple noble savages, either, with Ranquin, their chief, being a power-mad religious zealot, but there's not much Dicks can do in this page count to make any of the characters, human or Swampie, more well-rounded than Holmes did in his original scripts.

The rest of the novelization is Terrance's usual fare, adapting the camera scripts, and thrusting in barbs or covering up minor plot holes ("Several of [the Swampies] threw spears, though luckily all missed"). The text doesn't quite match the TV dialogue -- the word "hell" appears here in dialogue, though it was removed before taping; there's some extra exposition that also got cut, presumably for timing reasons (such as the Doctor explaining who Dame Nelly Melba was). In the book, Dugeen affirmatively identifies himself as an environmentalist spy for Sons of Earth, but the word "we" was neutered to "they" on the day of taping. Evidently the character Skart, the Swampie high priest, was not in Holmes' script for Part Four, until someone, probably the director, noticed that the character vanished and inserted him into the final installment by reassigning him lines from other characters. You can compare the book to the televised Part Four and see that Skart's on-screen dialogue comes only from words attributed to Ranquin or Varlik in the novelization.

But, oh boy, can Terrance write a death scene:

"Rohm Dutt's nerve suddenly broke. He began sprinting desperately across the swamp, leaping from tussock to tussock, blundering in and out of mud pools, crashing through the reeds like an elephant gone berserk. An enormous grey tentacle rose out of the swamp, flicked around his waist, and plucked him out of existence. There was a dreadful bubbling scream, a squelching, sucking sound - then silence."

Dicks' pacing of action scenes is something that brings me utter joy. He uses an intelligent array of words -- but none longer than three syllables -- and seems to perfectly match the action with adjectives, adverbs, verbs and even a simile. And the use of the word "silence" to represent "death". This book might have been written over a long weekend, but you could labor over rewriting Rohm Dutt's death for weeks and not come up with a more elegant passage than this one.

Really the one part of the book which is a letdown is Dicks' final sentence. The Power of Kroll was the fifth serial of the Key to Time season, with the sixth and final story coming up next. Dicks doesn't often lead into the next adventure, since the books were largely published out of sequence, but in this case, he notes that the search for the sixth and last segment of the Key to Time "was to be the most astonishing quest of all..."

Well, that would not quite be the case, come to find out...

The Kroll That Might Have Been by Matthew Kresal 9/2/26

The Power of Kroll. The penultimate serial in Classic Who's Key to Time season and the last Robert Holmes Doctor Who script of the 1970s. A four-parter that, it must be said, is not fondly remembered by Doctor Who fandom at large. Having recently re-watched it, that's understandable given everything from the cheap sets to a disengaged supporting cast and some of the worst model work in Classic Who's 26 year run. All of which might be blamed, at least in part, on that Holmes script. Or it does until you read the novelization from Terrance Dicks published eighteen months later by Target.

Dicks, as was the custom of the time, based his novelization largely off of the camera scripts for the serial and not what was broadcast starting in late December 1978. Thus going back to what by and large Holmes had written originally. A chance, after a fashion, to present the original vision of what the serial might have been.

Truth be told, it's an interesting experience. A lot of the broadcast serial is still here, to be fair, so the basics haven't changed. You still have the refinery with Thawn eager to see his project succeed, the Swampies with their leader's blind devotion to his squid god, and the gunrunner Rohm-Dutt trying to supply arms. Caught in the middle, of course, are the Doctor and Romana in search of the fifth segment of the Key to Time. Not much changes there.

What does change? The humor, for one thing, something that Holmes had been asked to tone down to begin with but which Tom Baker added a number of ad libs. A few humorous lines are still present (though whether scripted by Holmes or merely inserted into the camera script is unclear), but the result is that this version feels like what has sometimes rightly been termed "the Tom Baker comedy half-hour." Even going so far, at one point, as to explain who Nellie Melba was for readers such as their reviewer who were uniformed to make that gag work better. It's subtle but surprisingly effective.

With that change of emphasis, the focus returns to what inspired Holmes to begin with. Namely, that the serial offered his allegory for the treatment of Native Americans, forced onto reservations, now facing the possibility of being sent away by the same government interests. It's something that Dicks makes clear, highlighting it explicitly with a reference to the "Red Indians of Earth," which is about as dated a reference as how he referred to Jamaica in his novelization of The Smugglers at the other end of the decade. Something that is largely lost in its screen counterpart in a case where, like much of the more recent Chibnall era, the focus has been on execution rather content.

Which brings us to Kroll himself. One of the joys of Doctor Who in prose, as well as on audio, is that it will always have a greater visual effects budget than on-screen. Kroll, that giant squid worshiped as a god by the Swampies, realized (alongside the refinery) in model work that was out of date even with the Gerry Anderson series of the early 1960s. In prose, starting with the evocative prologue Dicks adds before the television serial kicks off, Kroll can be the towering and terrifying figure that he was clearly meant to be before the model work spoiled it. A towering kaiju-like figure that solicits worship from the likes of Ranquin and fear turned homicidal intent from Thawn. The final confrontation as the Doctor tangles with Kroll is presented as a genuine struggle, rather than the limply filmed contest broadcast and seen by fans for decades. The same is true for a number of deaths at Kroll's tentacles that Dicks, coming from a pulp background, clearly relished writing. Here, on the page at least, the ambition behind Graham Williams' request to Holmes for Doctor Who's largest ever monster is fulfilled in one of the prime examples of the value of the Target novelizations even in the age of DVD and streaming: the chance to experience these stories in a different light.

Though there is only so much Dicks can improve upon. The characterizations, usually one of the greatest gifts Holmes brought to Doctor Who, are still fairly bare. There are no double acts that play off one another, and characters like Thawn and Ranquin remain as single-minded as they were on-screen. Dugeen gets expanded upon slightly, but Dicks's wish to remain close as possible to what was broadcast leaves parts of the narrative as undercooked as they were at Holmes' typewriter. Perhaps it's true then that Holmes, writing his second script for the Key to Time season and his fourteenth in a decade for Doctor Who, needed to recharge his batteries, as so many of his trademarks are clearly lacking here.

It's clear that The Power of Kroll was never going to be the strongest script that Holmes produced for Doctor Who. Yet here in prose, adapted by his former colleague, it's far easier to see what Holmes intended the serial to be. For all of its remaining flaws, the novelization of The Power of Kroll shows that there was a decent Doctor Who serial lurking behind the cheap sets, less than stellar casting, and bad model work. No wonder then that Holmes would return to many of the ideas here from gun runners to greed and the playing of both sides again for The Caves of Androzani. It's reason enough to consider giving it a read and discover the intentions behind a serial less than well regarded and wonder what it might have been at the hands of a different director and designer.