|

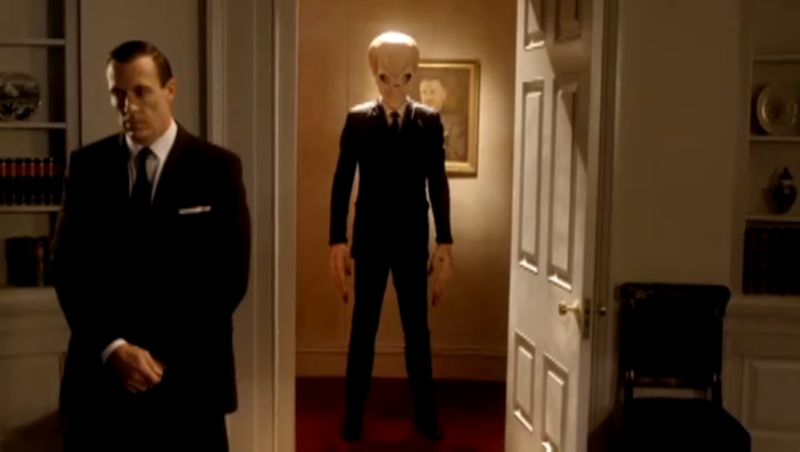

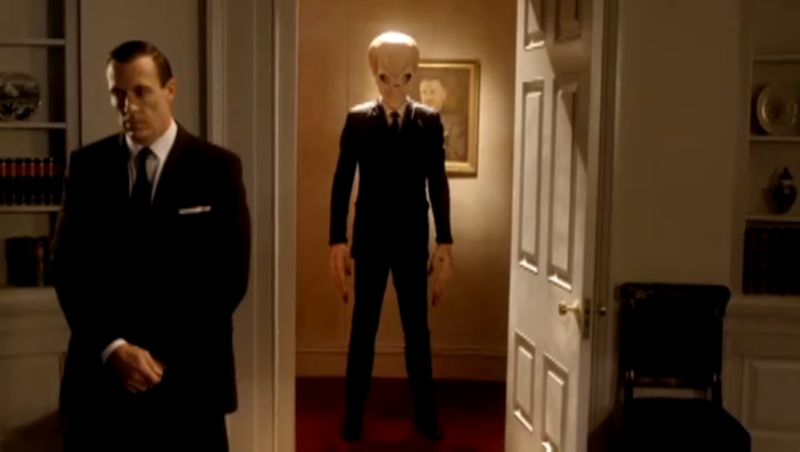

The Silence

|

Reviews

|

The Silence

|

"The church of the poisoned mind" by Thomas Cookson 6/12/16

For this article, 'Silence' refers to the religious order, 'Silents' refers to the genetically engineered creatures introduced in The Impossible Astronaut.

This is what I really liked about the idea of the Silence. They aren't a single race of monsters, but a multi-species religion and culture with followers and agents on many worlds. It's like that old Trek fan theory that Klingons might be an imperial culture consisting of various races to explain why TOS Klingons look so different to their TNG counterparts.

It's something I think Doctor Who could've done more often. Maybe having disenfranchised colonial human teens decide to join the Sontarans in the macho way of warriors or a 'friends of the Silurians' movement. Paul Cornell's Death and the Daleks even flirts with the idea of human fascists coming to follow Dalek ideals like a religion. It would've been cool to see something like that on TV.

But the Silence was something new. A multi-cultural, hierarchal religious network that had been amassing for centuries and considered the Doctor the infidel. They were pretty much what we'd been asking for in terms of new ideas and new foes for the Doctor to replace the usual Dalek and Cyberman stories.

They were also a tremendous gamble. Basing Series 6's whole arc on an unknown quantity.

Not since the Master's debut had the show gone in blind with a new foe whilst depending utterly on said foe being an instant success. The comparison's apt since the Silence were pretty much meant to be Matt Smith's own Moriarty or rather Moriarty's criminal empire.

Moffat probably believed he could pull it off. After all, his Weeping Angels and Gasmask zombies had been a success to rival the 60's Daleks, so it seemed plausible for him to catch lightning in a bottle again.

With a crushing inevitability though, I must conclude that the Silence didn't work. Certainly not for the stupendous task required. If the Silents appeared only in The Impossible Astronaut/Day of the Moon and the last we'd seen of them was getting their collective butts kicked by humanity, and there'd been no River Song arc fodder, they'd probably rank among the Weeping Angels and the Voc Robots as creepy monsters go. In fact, you'd have to go pretty far back to recall a time Doctor Who had been that frightening before.

The Androzani site ruthlessly dissected the Silents' dodgy physics. They seemed to overlook that, upon seeing a Silent again, you experience total recall of every time prior you have, so the TARDIS team collecting accumulated information on them isn't as impossible as they make out. But any holes in the concept could've been overlooked if they hadn't ended up being a mainstay of the season that the whole arc depended on.

In their first appearance, the Silents make sense as the product of a religious order, serving as a metaphor for religion's worse tendencies to blindside people. One could also see them as representing the influence of Nixon's media.

Many fans were horrified by the Doctor programming humanity to kill the Silents on sight. Even fans who'd defended McCoy destroying Skaro. But frankly the Silents' insidious control over humans and their willingness to kill our most vulnerable over minor irritations demanded a ruthless fight back and bloody revolution so that we'll never be that helpless again.

Nonetheless, it's easy to read the older Doctor's willingness to face the astronaut and accept his fate as a kind of penance for this.

From then on, aside from Madam Kovarian occasionally peeking in, we don't see the Silence again until A Good Man Goes to War. It's revealed that Amy has been their prisoner and that the Doctor's been travelling with a duplicate. This again hints the Silence are about having the all-seeing eye.

Unfortunately, come A Good Man Goes to War, it begins to seem Moffat's reasons for creating the Silence were skewed and wrongheaded. The Silence seem to exist just to facilitate (a) River Song's birth, (b) the Doctor having to fake his death and (c) giving the Doctor something to chestbeat against about how badass he is. But none of these are rewarding enough for such a convoluted arc, and they smack of neurotic, fannish indulgence.

Amidst everything we supposedly needed to know about who River is, I don't believe that included how she was born. The Doctor's death and escape was little more than a shock tactic, and the Doctor's all-important machismo amounted merely to gratuitous geek wish-fulfilment.

It's true that older stories like Delta and the Bannermen maybe could've used the idea of the Doctor gathering an army of his own personal dirty dozen against his enemies. I can even understand Moffat's fannish anxiety that this represents a crippling absence to the character's past, especially if you're concerned about your childhood hero now seeming like a fey nerd that his enemies would hardly fear.

But this early into Matt Smith's run, it just doesn't feel like the time for it. It's too soon to push his character that far. As Diamanda Hagan pointed out, why doesn't the Doctor just materialise his TARDIS around Amy and baby and then leave? Well because we need to set up River's assassination of the Doctor. But this all depends essentially on the audience caring.

As the Doctor describes to Vastra, there's a multitude of variables in River even existing at all. She's been a constant presence before, during and after events that even led to her own father never existing. Yet her timeline and existence remains fixed in spite of that. But that's something the audience can go along with, if it's ultimately a story that's interesting and worth telling.

This one isn't. And part of the reason it's so impossible to care is that Moffat has set up an enemy that could have zapped the Doctor in the back any time, so why must they go these elaborate lengths to create River, who must kill him at lake Silencio on that particular date? It's hard to care about an enemy's long game that's so handicapped and neurotic.

The assumption seems to be that we'll care because we cared about River back in Silence in the Library and so we'll care about discovering her story here. Again, this is echoed in Moffat's dismissal of fan requests to bring back the Rani by saying "No, because she wasn't memorable enough". River is apparently in recent enough memory to be worth this indulgence.

The problem is, the River we met in 2008 and the River we discover the backstory to here might as well be completely different characters, and the result of this 'let's keep bringing her back because people remember her' is that by the end of the season we never want to see her again.

Okay, please indulge me going over the problems of River again, and how she ended up becoming such an insufferable element of Moffat's era. It's telling that, back in 80's Doctor Who, the closest thing we got to River Song was the character of Wrack in Enlightenment, in a story that went out its way to villainize and punish her wanton sociopathy, not reward it.

It's not just morality that's changed about modern TV. It's more depressing than that. Ever since Big Brother started, it seems viewers have become honestly fascinated by the insufferable and will watch John McCrick being a nasty, petty, misogynistic cad.

There have been TV grotesques prior, but they were usually carefully handled. For instance, Bottom would've probably been unwatchable if its slimy, lecherous leads weren't regularly punished by beating each other up for our amusement. Back in the 70's, Tom Baker's Doctor was something special at a time when most American showmakers would've feared such a gregarious, smartarsed protagonist might come off as insufferable to the audience. It was rather a depressing, reactionary and macho cinematic era where protagonists had to be of few words (restricted to the kind of functional dialogue that Tarantino spent his film career backlashing against), but the language of violence was unlimited, commonplace and ubiquitous.

Audiences usually hate a Mary Sue like River Song when she isn't seen to suffer real consequences or take punishment occasionally. But, simultaneously, audiences are understandably uncomfortable about seeing female characters violently mistreated, unless the reward is seeing her get her revenge (which seems like the real road not taken with River, given her exploitation by the Silence). In Lucy, the source of Scarlet Johanson's temporary Godlike powers was simultaneously slowly killing her, thus establishing a ticking clock and something continually at stake. Sometimes even this doesn't work. Buffy's character got regularly punished during her later seasons, and it didn't make her or her horrendously misandrous show (which should've ended when Angel left) any more tolerable.

But this gets to the heart of the problem. Even if the Silence were well thought out, the product of their machinations is River Song, who by then was such a God-mode Mary Sue who could do anything she wanted without abandon and was untouchable by any consequences that she just didn't feel like a real part of the fiction at all. Her very presence broke the spell.

Game of Thrones has attracted enormous controversy for its scenes of rape, torture and abuse, but anyone knows it wasn't written this way out of sadism, but because the author understands the ugly fundamental truths of what humans are capable of. It's meant to outrage and upset us, because it reminds us of our decency and compassion.

The problem is that any sense of outrage just seems to be completely absent concerning what the Silence have done to Amy, how they've terrorised her, devastated her life and robbed her daughter of her childhood. By the rest of the season, she seems perfectly fine and the show just carries on like business as usual.

The terrible things the Silence did seemed to have happened not to inform this show's sense of morality but for purely functional, mechanical purposes of showing River's origins in payoff to a teased reveal. Moffat's only motivation seems to be feeling personally smug about it, which makes the whole enterprise feel sociopathic.

So the Silence are completely neutered as an enemy because our sense of outrage at what they've done is neutered, and it's treated like it doesn't matter. Furthermore, the Silence's motivation for wanting the Doctor dead is barely an afterthought. The Daleks hate the Doctor because he's determined to destroy them, as they stand against everything he believes in. Varos' population hated the Doctor because to them he was a threat to their economy. The Master hated the Doctor out of personal jealousy.

But the Silence? What drives their fanaticism?

Unfortunately, that's something Moffat keeps changing his mind about. Initially, River said their actions were based on fear of him, and his behaviour of being a law unto himself and recklessly sabre rattling his enemies. And we had to take her word for it.

But in The Time of the Doctor, in the Silence's final appearance, Tasha explains this had nothing to do with it, and they just didn't want him to land on Trenzalore.

We'd been teased by the mystery of who blew up the TARDIS in The Pandorica Opens/The Big Bang, but I think it should've remained a mystery. That story opened up the Doctor's rogues gallery enough to make potentially anyone from his history a likely suspect, so I feel they could've remained anonymous.

But no. Tasha reveals the Silence were behind that too (presumably with a single Silent infiltrating the TARDIS and acting as suicide bomber).

Bit of a ridiculous effort for such a flimsy, half-arsed reason. This off-the-cuff revelation provides no ideological catharsis, because ideologies and motivations just shift on a dime in Moffat's writing. The Doctor has nothing substantial to argue against or prove wrong.

And that's disappointing, because for all the Silence's deeds and devotion to their cause, we'd all assumed some higher purpose was behind it.