THE DOCTOR WHO RATINGS GUIDE: BY FANS, FOR FANS

|

BBC

A Town Called Mercy

|

|

| Story No. |

249 |

|

| Production Code |

Series 7, Episode 3

|

| Dates |

September 15,

2012

|

With Matt Smith,

Karen Gillan, Arthur Darvill

Written by

Toby Whithouse

Directed by

Saul Metzstein

Executive Producers: Steven Moffat, Caroline Skinner.

|

|

Synopsis: A gunslinger is chasing a criminal in a town in

the old west.

|

Reviews

"Spectre of the Gun" by Thomas Cookson

18/4/14

This isn't to blame Moffat, but I really don't think this split season

approach is working. There are many suggested reasons of why it's being

done, whether it's a BBC decision or Moffat's own. If it's being done to

save money in these times of recession, I guess that's one more thing we

have to grin and bear. If it's being done because of Moffat's other TV

commitments he needs to work round, then no wonder he's been losing his

focus lately. But if it's being done because of ratings, to try and save

the show from a mid-season lull, I just think it's highly

counterproductive. It's the very length and continuousness of a season

that gives it a wide profile and maintains its momentum. This is making

the show far easier to miss, and is actively damaging its momentum. I

think its effect is more frustrating than tantalising to viewers.

But the unfortunate side effect of the split season is that a five

episode run still has to sell a sense of constant variety about the show,

with each new episode. This is probably why all two-parters have been done

away with now. It has to be a different story every week, to make the most

variety of what little time of the year they've got.

Frankly, the 45 minute standalone format has always been problematic,

leading to over-frenzied, nonsensical stories with forced urgency and on

the nose hyperbole. Even the successes of The Unquiet

Dead, Dalek, Girl in the

Fireplace and even The Doctor's Wife

somehow felt like they had something missing, or weren't entirely all they

could have been. Lacking time to develop Reinette and her romance with the

Doctor, or deliver a more appropriate, bloody climax to Dalek in Salt Lake City, or establish a scene where the

Doctor takes Rose back to 2005 to reveal that Gelth zombies will rule the

Earth if not stopped. In fact, to my mind, the only two stories to

entirely succeed at being mini-masterpieces are Blink and The Girl Who

Waited. But never has the format failed more consistently than in the

whole first half run of Series 7.

The biggest blow of this is in terms of the final days of Amy and Rory

Pond. As I said in my Let's Kill Hitler review, I

really do suspect that the Ponds' natural endpoint was A Good Man Goes

To War, and that, once Moffat had written that, he grew weary of them

both, and only kept them around out of obligation. I'm not sure why the

Ponds are still here in Series 7 since the closer of The

Doctor, The Widow and the Wardrobe (i.e. the only part of that

terrible story that's worth anything) would have been a fitting goodbye to

them, and Series 7 would have a slate clean to establish the Doctor with

someone new from the outset. But I'm still hard pressed to believe that

Moffat cares about these characters anymore. I think this is the part of

Series 7 that Moffat just wants to get out the way so he can move onto

whatever high concept he has in mind with Clara. I mean seriously, Moffat

practically left the bulk of this half of the season with Chris Chibnall,

in a move that makes me seriously dread Moffat's grooming him to be his

future replacement.

You may get the impression I want them gone, but, on the contrary, in

the anticipation of Series 7, and in key moments of Asylum of the Daleks and The Power of Three, I felt a strange melancholy

about knowing of their departure. I knew it was going to break my heart

and that I was going to miss them, and that somehow it would mark the

premature end of something wonderful, before its time. I couldn't care

less about any of RTD's companions in the end, as excessive attempts to

make me care about them just left me sick of them in the end, except maybe

for Donna. But I loved Amy and Rory. Why couldn't they stay?

My feelings were mixed, however, because I also knew that the events of

Series 6 had caused them to emotionally flatline, thus damaging my

investment in the show badly. Basically, there was a huge elephant in the

room that Moffat couldn't deal with, and so the only option seemed to be

to throw the baby's parents out with the bathwater. In other words,

because of the domino effect of missteps of Series 6, Amy and Rory had to

leave. It's a shame because, if not for that, they could have probably

gone on as a team for several more seasons.

But there's a problem. As a one last hurrah for the Ponds, Series 7 has

been an incredibly limp one. And I suspect part of the problem is that it

almost feels like they could leave on any of these five stories and it

would make no difference. So that raw feeling I had of anticipated

heartache after Asylum of the Daleks turned

very quickly numb in the following week as Amy and Rory were treated as

superfluous to the Doctor's new gang in the frighteningly generic Dinosaurs on a Spaceship. It was a

crushing sense of how their precious time left on the show was being

wasted and squandered. And it didn't help that there was a lack of any

emotional carry-through from the events of Asylum

of the Daleks. I mean, the last thing the makers should be using now

is the character reset button.

Sadly A Town Called Mercy was worse in terms of marginalizing

Amy and Rory into the most superfluous presence, thus leaving The Power of Three the task of performing

emergency surgery to rectify this. They needn't be in this story at all

frankly; arguably, the story would work better if the Doctor was

completely solo, and it was one of the townspeople who had to pull him

back from the brink. In terms of speculating on behind-the-scenes

decisions, maybe they should have moved this one further into the season

and replaced it with one that used Amy and Rory more substantially. The

one slight snag would be that then it would be Clara who got neglected in

this story, and I think Moffat judged it more important that Clara wasn't

neglected. But since it's only Amy and Rory's third-to-last story, it's

perfectly fine.

And you know, I wish Moffat would have moved the story later on,

because this script seriously needed more work. It's incredibly

half-baked. In fact, the story actually felt like a work still in progress

as I was watching it. The usual criticisms have been made elsewhere. That,

with the exception of the Sherrif who dies halfway through, the

townspeople are all criminally undeveloped to the point of anonymity. Even

the very girl who turns out to be the narrator gets zero development.

Jex's character shifts on a dime inconsistently from scene to scene, until

it's no longer clear what kind of man he really is. A lot of this story

suffers from a bad case of ignoring the rule of 'show, don't tell'. As a

result, we don't get to see what kind of man Jex is; we're only told

through his all-too-contrary dialogue. The Doctor's moral predicament

feels so dictated and recited that it lacks the mythicness it needs, even

though the Doctor's speech about his merciful failings feels like it was

written specifically for me.

No wait, there's a bigger problem than that. See, the scene when the

Doctor forces Jex over the line at gunpoint is really riveting stuff,

right down to the moment where the Sherrif dies protecting the man the

Doctor was about to turn over. It has a big impact, which speaks of how

potentially this story could and should have been great all round. From

that moment on, nothing seems certain. The Doctor has come so close to

crossing the line only to find he can't do it at all, even knowing the

town's population will be forfeit. And in any case, lives have been

committed and lost to protecting Jex.

But, in the end, I came to realise there's a problem with the moral

dilemma. Which is that it dodges the third option completely unawares. The

choice is framed as simply "hand over Jex, or the entire town faces the

Gunslinger's wrath", in his own words. The third option then is obvious.

Kill the gunslinger. If the Doctor can't kill the condemned man, then he

must deal with his executioner. Unlike Jex, the Gunslinger is armed and

has already declared his intent that he will kill innocents if not

stopped. There really isn't a moral question here. It's him or them. And

once the Doctor's nearly crossed that line, it's hard to accept he won't

even consider the lesser of two evils.

The reason why this solution doesn't come up is that the story seems to

be operating on the assumption that the Gunslinger is meant to be

indestructible, despite apparently being the vengeful lone survivor of his

squadron. But the story never actually demonstrates this. No one even

tries shooting the Gunslinger. Had they done so, then maybe the threat

would be more greatly established and those nagging questions would be

gotten out of the way.

Unfortunately, the Gunslinger just isn't an interesting or formidable

enough antagonist to carry the story. I can't help but feel that so many

problems with this story's jeopardy and drama could have been solved if it

had been a gang of cyborgs hunting Jex down. It would have added to the

odds in so many ways. Our heroes may easily slay or dissuade one of them,

but not all of them. For some reason though, the makers seemed to go

instead with the Western cliche of the lone gunslinger. Or, more

accurately, the Westworld model. This strikes me as odd since the four

horsemen of the apocalypse idea would be better.

There are also those who claim the Gunslinger works in the same

unstoppable terms as the Terminator. Which I don't get, for two reasons.

First, the aforementioned failure to establish how indestructible he is.

Second, the Terminator works because of his relentless determination, his

directness of motive and his lack of scruples. Frankly, the Terminator

would suck as a villain if he suddenly took pity on his target at the last

moment and decided to change its mind. Seriously, the audience would throw

things at the screen. Having an indecisive villain who conveniently gives

up at the end just doesn't work. And this is again why a gang would be

more formidable and workable. If one gets cold feet about killing, the

others will remain a threat.

And I really don't get the Doctor's plan here, of giving several people

Jex's birthmark so that the gunslinger has to identity-check each one of

those living decoys. It's as if the story changes its premise from scene

to scene. It was established by the Gunslingers' motivation that he would

kill all the villagers to get to his prize, and yet the Doctor decides the

answer is to draw a bullseye on them all. And, for some reason, it works

and the gunslinger now can't kill without a positive identification of his

man, and this business of checking each face slows him down. And,

eventually, no one has to die. No one even has to fight. The enemy just

changes his mind and lets everyone live.

I put this down to being a rushed effort, and a potentially expansive

story that had to be cut short unceremoniously to fit the 45 minute

runtime, and so had to be given the most pat quick-fix resolution to both

the predicament and in the service of proving the Doctor made the right

choice, even if the plot has to contrive to valorise his stance

unrealistically.

In the end it all feels just a bit too easy.

Look Around You by Mike Morris

14/3/15

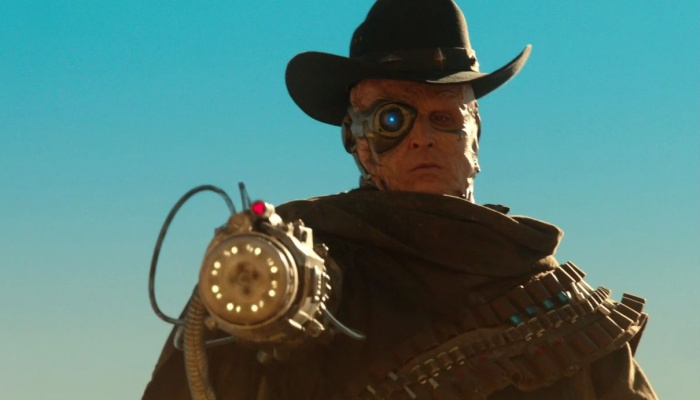

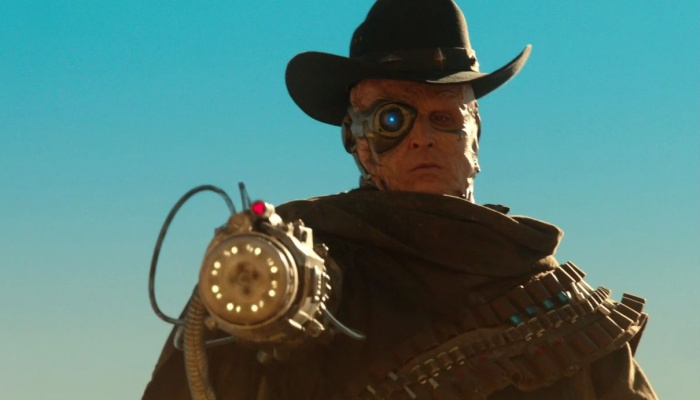

A Town Called Mercy doesn't really work. It's got a lot of great

things in it, and the sight of a cyborg soldier stalking through a town in

the Old West is the most striking visual image of the Series 7A

mini-season. But it doesn't really work.

What makes that a little painful to write is that A Town Called

Mercy really should have been the best damn Doctor Who story

we'd seen for ages. It's a Western, and they've finally made at a time

when Doctor Who can actually achieve a convincing environment to do

this sort of thing properly. A few years back, the TV show Deadwood showed

how you can boil an entire, historically alien culture down into a single

town just by dialogue alone (although Doctor Who would probably

want to avoid repeated use of the word "cocksucker") and Westerns have a

timeworn ability to suggest vast, harsh landscapes on a minimal budget.

It's such a good premise that you wonder why it took the new series brains

this long to think of it, especially now we've all stopped pretending that

The Gunfighters was rubbish.

A Town Called Mercy is the standard-issue story of a lone gunman

comes to town, looking for a fugitive with a dubious past - but then the

Doctor's dropped into the mix, and the genre tale is twisted into

something new. The fugitive's an alien war criminal; the gunman is a

cyborg. We've got two worlds suggested - the Wild West and the alien world

of the Kahler, trapped in a nine-year war. The two collide. And then the

Doctor, himself a survivor of a cataclysmic war, becomes embroiled. This

has everything it needs to be magnificent.

In fact, it's... okay.

Actually, if anything, it's kind of drab. There are conversations about

the horror and morality of war, which should be fascinating, but

there's no sense of - well, the best word I can come up with is weight,

the sense that people are discussing these things because they matter to

them, right there in the story. More superficially - but perhaps related -

is that the cyborg should be both terrible and terribly sad, but for some

reason it doesn't look anything more than technically impressive. Come to

the end and - to pinch a line from About Time - you feel like

someone's told you about a great story you'd like to see for yourself

sometime.

Since I've invoked About Time, it's worth mentioning that both

authors of that series - particularly Miles - are convinced that the

primary mandate of Doctor Who is to take the viewers to "strange

new places." While it was the show's earliest recognisable mandate, it

wasn't universally true - there are many Doctor Who stories where

the setting and environment isn't important at all. One couldn't look at

stories as varied in both tone and quality as The

Ambassadors of Death, The Time Monster, The Seeds of Doom, Earthshock and

Terror of the Vervoids and ask anyone to believe

they seriously suggest environments that are self-sustaining and

unfamiliar. As for the new series... well look, Series One never left

Earth, for crying out loud.

All that notwithstanding, it's still true that the majority of

Doctor Who stories take the viewer somewhere strange. Stories like

Genesis of the Daleks, The Face of

Evil and Kinda manage to "shrink" a feasible

environment, comic-book style, into an analogue that makes sense within

the confines of what television can do. More common is the tactic used in

stories like The Robots of Death, Horror of Fang Rock, Enlightenment

and The Greatest Show in the Galaxy, which - through

dialogue and attention to detail - manage to hint at a larger world beyond

the edges of the screen. There is a sense of scale to these stories, even

if some of them have limited scope; the unknown world of the lighthouse in

Fang Rock and the society that gave rise to it, is as

interesting as the space-and-time-spanning civilisation of Enlightenment's Eternals. To take this argument into the

new series, we can point to Moffat's jointly-best-remembered work - The Empty Child - and see the way the Blitz

becomes a character in itself. Just as the nanogenes have twisted human

beings out of shape, World War II has worked its way into the corners of

this society and turned it into something horrific. It's a drama of

environments.

However, the majority of the Moffat era up to A Town Called

Mercy had fashioned itself after his other jointly-best-remembered

work, Blink. They're about plotting, the exploration

of SF concepts and monsters to scare kids. The Doctor usually knows almost

everything about the planets he visits, and many of them tend to be

sketched-in. This is even made into a joke in Amy's

Choice, where the things-that-live-in-old-people are given a

deliberately generic and uninteresting backstory. The best of these

episodes - The Girl Who Waited - is illuminated

by nice design, but there's little sense of exploration or a wider world

that underpins the one we see.

All of which is to say that, given that Westerns are effectively all

about their environment, you can probably see where the problems might be

with A Town Called Mercy.

Not that it doesn't get some of this right. A Town Called Mercy

is beautifully shot. For once in the New Series, the trip to foreign

climes has worked; we really get a sense of the heat and dust and creaking

floorboards, the visuals alone conveying this place as somewhere with a

shaky toehold on existence. There are some good performances in here too,

and the preacher calling out the lord's prayer is as atmospheric a scene

as has existed in Doctor Who for ages. The Terminator-thing

exploring the town, is one of the better a sequences of Series Seven.

And yet as a place, Mercy always feels like... television. A

construct, if you like. Aside from those who play the roles stereotyped by

movies (Sheriff, Bartender, Preacher) we don't know what anyone in this

town actually does. We're told that people are starving, but we don't see

where their food comes from. It's mentioned that nobody can get in from

outside, but there's no sense of geography - how far is it to the next

town, for example? What's it for, this village of eighty people?

Agriculture? Trade?

These are all small questions unaddressed, and, while each of those on

its own might not add up to much, that's the kind of subtlety that makes a

place really convincing - and therefore make the drama feel like it

matters. There are bigger absences from the drama, too. This is - clearly

- a very religious place; an abomination coming from beyond the stars

should cause a huge crisis of faith. Yet... well, the preacher just

says his prayers when the scene needs some drama, and everyone shrugs off

a cyborg from outer space as being no more unnatural than The Man With No

Name.

As for the Kahler and their war... what have they gone to war about?

Their technology tells us nothing about them, Jex speaks like a human in

all but name, and it's never particularly clear if he's a war hero or a

war criminal. The conversations between the Doctor and Jex are about

important things, and there are some good lines - I particularly liked the

one about how you don't get to choose your own punishment - but without

convincing backgrounds these arguments just seem to float, the verbal

equivalent of a badly-CSO'd Stegosaurus in Invasion of the Dinosaurs. Adrian Scarborough is

an excellent actor, but as Jex he seems unsure whether he's an unrepentant

soldier or burdened with guilt. It's hard to blame him; the script doesn't

treat him as a real person so much as a vehicle for hitting back and forth

about the nature of war, guilt, justice and vengeance until he blows

himself up to shut down the narrative.

Now, deep breath before the next bit-

Matt Smith gives a rather uneven performance.

Now, I didn't want to believe this at the time, since I'd long held

that Smith was the show's best asset. However, there are points in Series

Seven where he seemed to drag on the show, and this is the first of them.

He overplays the comedy-western shtick and it's not funny as a result. As

for the scene where he throws Jex out of the village - which should be the

centerpiece of the whole of Series 7A, really... well look, there's no

nice way of saying that it's a terrible scene and he's terrible in it. I

think the intention is that this picks up on the Doctor's actions at the

end of Dinosaurs on a Spaceship, but

it's not well-scripted and Amy saying "We don't do this" has no insight at

all. And yet all that's a sideshow to the main problem, which is that

Smith plays it as an ineffectual bully and, really... well, it's

embarrassing.

And yet more than that, the scene that sums up this story's problems is

where the Doctor faces a man who's pointing a gun at him and convinces him

to do something better. It should be wonderful, except... we don't know

anything about who this man is, or what he's lived through. The Doctor

tells him "violence doesn't end anything, it just leads to more violence,"

and the formal language jars horribly with the setting - that's

parlour-room morality, it isn't what you say to an eighteen year-old who

lives in constant poverty and fears for his life. It doesn't belong in the

old west, it belongs in the writer's front room when he's gently scolding

his children.

If all that makes this sound like a complete waste of time, it's not

bad; it's just got a lot of good elements, which fail to come together and

needed at least one more draft. The visuals stayed in my memory, more so

than any other story this season. The discussion about morality in war is

diverting enough on its own merits, even if it never really leaves the

page. And although they aren't given a great deal to do, Gillen and

Darvill are great. Plus there are little touches which really sing - I

love the way the cyborg moves, for example, even if it doesn't impact the

story all that much.

So: A Town Called Mercy doesn't really work. Still, I wouldn't

say I dislike it; even if it is a collection of bits rather than a

properly cohesive tale, some of the bits are enough for me.

Travel alone for too long by Hugh Sturgess

3/11/19

At the time, this was one of the better episodes in the first half of Series 7. It is still clearly superior to Chibnall's two efforts, mainly because it looks like a piece of television that exists to tell a story with a purpose, rather than just fill up forty-five minutes of the TV schedule with something tolerably entertaining labelled Doctor Who. That said, being an above-average story for Doctor Who in 2012 is not much of a recommendation. It displays the same tiredness and almost carelessness of its stablemates, albeit in new if equally painful ways. Dinosaurs on a Spaceship's chief sin is that is a fundamentally pointless piece of TV that systematically avoids making any interesting decisions. A Town Called Mercy is trying to say something important about the Doctor but still systematically avoids making any interesting decisions. For the clumsiness of its execution and the sheer dreariness of its decisions, it's fairly terrible.

A Town Called Mercy is, in essence, another of those stories wherein the villain accuses the Doctor of being no more morally superior than the villain him/herself. The best known example is Davros's lecture in Journey's End, which accuses the Doctor of shaping his companions into "weapons" as much as Davros systematically experimented on his own kind in order to create the Daleks. Despite the transparently ludicrous moral reasoning involved here, the Doctor is shamed into silence and looks very troubled and guilty - this, of course, being the aim of the exercise. Authors love to roll this out not because it genuinely problematises the Doctor's heroism, but because it serves to make him flawed and tragic and thus more noble. The Doctor is such a good man that he is liable to feel guilty after a scolding from evil incarnate. A genuine critique of the Doctor as somehow as bad as his enemies would require us to feel dislike for the character as some point - which these stories never do. The core line of this episode - "...all the people who have died because of my mercy" - gives the game away. The Doctor's chief character flaw, this line says, is that he is too much of a nice guy, even to evil people.

So here the Doctor is compared to a character inspired by Josef Mengele. Mercifully (ha), the episode doesn't commit to this idea, merely using it as a way to wind up the Doctor to the point he's prepared to sacrifice Kahler-Jex to the Gunslinger. Isaac dies to save Jex, and the rest of the episode is presumably the Doctor learning... something.

This is where the episode's main problem lies. What lesson are we meant to conclude the Doctor learnt from this experience? "People can change and make amends for their past sins," I guess, which is a vapid moral point that would allow an unrepentant war criminal to evade justice because he's been nice to people since, but at least it's a coherent point. But how should he act on this? He should show mercy to his enemies or else he'll... be like Jex? The similarities between the Doctor and Jex - both doctors who did something terrible to win a war - are obvious and make for another of the many echoes of The Day of the Doctor in Series 7. But Jex's sin was not that he failed to show mercy to evildoers. The episode never commits to the Doctor/Jex parallel, leaving an unfocussed moral thread to the story.

The character arc the episode wants to tell - that of the Doctor being forced by Isaac's dying request to protect a man who committed an atrocity - is rather undermined by the resolution to the episode, in which Jex commits suicide. This outcome could have been achieved at the halfway mark, had Isaac not thrown himself in front of the Gunslinger's blast. For the episode to explicitly reject that neat and tidy outcome, only to fall back on it at the end, makes Isaac's death irrelevant and whatever message the Doctor was supposed to learn about second chances void. The episode's message thus becomes: even those guilty of terrible crimes can redeem themselves by doing good, if we show mercy - or, better still, they can be guilt-tripped into committing suicide and saving us the moral quandary.

None of this is helped by the character of Kahler-Jex. I don't think we can blame Adrian Scarborough's performance for the problems with the character, though he does not even try to fix those problems. Jex is wildly inconsistent, alternating between a guilt-wracked veteran and a remorseless war criminal, often within the same scene. His characterisation flicks between the two depending on which will most annoy the Doctor at the time. The most obvious example is his bizarre decision to taunt the Doctor in the lock-up over their supposed similarities (similarities Jex discerns entirely through the look in the Doctor's eye), accusing the Doctor of being a coward, etc., only to then dissolve into gaping terror when the Doctor drags him outside the town to face the Gunslinger. Why on Earth would he go so out of his way to alienate the people risking their lives to protect him? The character no longer exists - he is simply a vehicle for the moral point.

The script tries to get around it by giving Jex a line that it "would be so much easier if I was just one thing". Indeed it would be, because then we could focus on an actually consistent character. The argument that people in real life are complex and contradictory does not work here. A Town Called Mercy, like all of Series 7, is a very heightened depiction of the world, so arguing that the character of Jex seems unsatisfying only because of its auteur-like commitment to realism is obviously ludicrous. Jex is not a fleshed-out, nuanced character; he's a moral puzzle to tweak the Doctor. Literally the only purpose for which Jex exists is to flick between guilt at his crimes and pride in them, so as to confuse and anger the Doctor. He proudly calls himself a war hero and gloats that the Doctor wouldn't have the guts to do as he did, then pivots instantly off the Doctor's righteousness to simper about the guilt he carries with him. This is so obviously done to drive artificial conflict that it's impossible to invest in it.

And this artifice is what his entire character is built around! The episode has neither the time nor the patience nor the skill to depict a genuinely nuanced character who deeply regrets his actions yet is also proud of them, and what it has instead is a character who is either all regret or all pride. Jex is the episode's central character, and yet he's a pure story vehicle to bounce off the Doctor.

So we have an episode built around what it meant to be a deep moral quandary, which is entirely hollow. In a way, the rest of the episode could be as good as anything, and this would still be a near-fatal problem. Sadly, the rest of the episode is merely "as good as most of Series 7", which is a pretty dire judgement given the lowly place Series 7 ranks in the pantheon. That said, the efforts of the production team to recreate the Wild West are gorgeous, although it's very clearly Themepark History. Like all the genre transvestism of Series 7, it's a huge amount of fun seeing the show put on the clothes of a vendetta Western for a week. Purely on the level of visuals and atmosphere, A Town Called Mercy is terrific.

The moral dilemma is non-existent, and although Matt Smith still gives it a fair fist, in many ways his performance has become grating, a marker that he has run out of anything interesting to do with the character. Arguably, Smith was at his best before the writers knew what his performance was going to be like, so his flourishes came on top of the script rather than be given acreage of space by the writers. Karen Gillan, meanwhile, is simply phoning it in, but you can hardly blame her given how bland her role in the moral dilemma is. She's required to be the good angel on the Doctor's shoulder, offering trite statements like "This isn't how we work." This from the character who consciously left Madame Kovarian to die in agony in The Wedding of River Song - and was right to do so!

A Town Called Mercy illuminates a lot of what is wrong with Doctor Who circa 2012, in its haste and carelessness. But it also shows the weaknesses of the very form that Doctor Who in 2012 was beginning to move away from. One of the chief innovations of the new series in 2005 was to put the focus on the Doctor as a character with an interiority, rather than a vehicle into strange new places. This took the form of what Lawrence Miles called "Doctor weepies", wherein the actor playing the Doctor is given the chance to emote like hell (anger and hatred in Dalek, variations of sadness in The Girl in the Fireplace, Human Nature and The Doctor's Daughter). This genre radically reshaped our understanding of the Doctor as a character, but they had the side-effect of normalising the Doctor, making him seem like a regular human being. What was not obvious about Series 7 is that it marks the point at which the series begins to become uninterested in the Doctor as a character. The disconnected "movie of the week" structure to the season, as opposed to the more serialised, arc-driven structure of previous years, puts the focus back on the story rather than the evolution of the characters from episode to episode. A lot of Moffat-era Who either hits the reset button between episodes or has wild leaps for the characters (Clara changing houses and jobs is the best example).

Essentially, episodes like A Town Called Mercy become impossible by the time Capaldi takes over, and not because his Doctor is less amenable to sympathetic portrayals of his angst. Whithouse's next story is Under the Lake, which is dreadful but in totally different ways to A Town Called Mercy.

He's called Susan. And he wants you to respect his life choices. by Evan Weston

4/11/19

The Western happens to be my favorite film genre, particularly the Italian Spaghetti Westerns of the late 1960s and early 1970s, so I'll admit I was particularly excited to view A Town Called Mercy. But weirdly enough, the Western is not a genre that melds particularly well with Doctor Who, which at its core is a sci-fi show. That's not to say the two genres can't blend - anyone who's seen Firefly can certainly attest to that - but Doctor Who is explicitly a show for families, and the main themes of the Western are built on very adult pillars. There's the brutality and inhumanity of the Old West, the carefree violent spirit that defined the men who crossed it, and loads of language and misogyny to boot. Doctor Who doesn't exactly delve into that sort of thing, which makes A Town Called Mercy a bit of a half-hearted effort when it comes to really doing a proper Western.

That said, they've certainly got the look and all the trappings down. Marcus Wilson dragged everyone out to Spain for an on-location shoot in one of Sergio Leone's original Western sets, and the result is perhaps the best-looking episode of Doctor Who ever produced. Saul Metzstein once again proves his mettle behind the camera, and he captures the sweeping landscape in all of its majesty and loneliness. There are tons of long nature shots, all to show how very isolated this little tale is, and Metzstein enforces this wonderfully. The costumes and the genre conventions are spot on as well - thick Southern accents, the kind but stern marshall, the townsfolk rising up against the man trying to protect them - and A Town Called Mercy certainly does the best it can to be an authentic homage to the genre, Doctor Who style.

Never is this more apparent than in the remarkable Gunslinger, given form by the hulking Andrew Brooke. The Gunslinger is the perfect sci-fi western cyborg, with an automated eyepiece and an awesome space gun paired up with several rounds of ammunition (not that he needs it) and a terrific cowboy hat. He looks absolutely fantastic and is shot in a way that makes him incredibly menacing. The Gunslinger loses some of that initial scare factor once the plot makes its few twists, but for the first half of the story he's a swashbuckling, terrifying villain.

The villain in the latter part of the story is Adrian Scarborough's Kahler Jex, the alien doctor who experimented on his own people in order to win a war. Scarborough's performance oozes menace and intelligence, but the script sort of short-circuits Jex after its big reveal. While his moral sparring with the Doctor consistently manages to be entertaining, he never really steps outside of a gray area, and thus the resolution to his character doesn't have quite as much power as writer Toby Whithouse seems to think it does. Suicide isn't a noble means of escape for anyone, and while that portrayal is a tad offensive, the rest of it is just poor writing. This was a story screaming for an imposing bad guy, and Jex just wasn't it.

Really, the last 20 minutes are a bit of a mess, and that's by far A Town Called Mercy's biggest failing. Unable to provide a Mexican standoff or any sort of gunfight due to the nature of Doctor Who, Whithouse decided to turn the story into a moral parable. This would be fine if there were any doubt which side was correct, or if I thought for a second that Whithouse would actually force the Doctor to make a decision. Instead, everyone wrings their hands for a while and the Doctor confronts the townsfolk while we wait for the big finish, and then the whole cast runs around for five minutes only for Jex to blow up his own ship. That's not good dramatic storytelling, and A Town Called Mercy is probably Whithouse's most stunted narrative to date. He's a strong writer, but there just isn't enough here for this to be a great or even very good story.

It's not for lack of effort from Matt Smith, though. Number Eleven turns in a third consecutive stalwart performance, entrenching himself in the role deeper than in his first two series. Since his phenomenal turn in Closing Time, Smith has been on point in virtually every story, and this continues through to the end of his run. He had a rockier start than his two predecessors, but his chops as an actor were never in question, and I believe he outshines the Tenth Doctor by the seventh series. He almost convinces us that the moral quandary in A Town Called Mercy is worth discussing, his performance filled with furrowed brows and a look in his eye that says, "I'm too old for this." The Time War isn't name-checked, but the parallels between Jex and the Doctor are implied and hinted at over and over again, and these moments are Smith's (and Scarborough's) best. Unfortunately, Whithouse doesn't quite know what to do with the Ponds, who are given less to do than in any episode I can remember. Amy gets to walk the Doctor down from the brink when Jex is discovered, but after that she's just a pretty face, and Rory is literally just there for the entire story.

So it's not a true Western, and it's not a great Doctor Who story, but there is a lot to recommend in A Town Called Mercy, which ends up proving itself a fine piece of mid-season filler. This sort of story becomes the template for Series 7, though - strong production and good central performances inhabiting a script with a few too many screws loose to be great. A Town Called Mercy might be the one with the most potential out of all of them, being a Western, but the genre's nature also limits it, and in the end we're presented with a watchable but inconsequential episode of Doctor Who.

GRADE: B